Sunday, December 21, 2025

139. Jesu, Meine Freude, BWV 227

composed by Johann Sebastian Bach

The definition of “motet” is exceedingly vague. Ostensibly, it is usually a short multi-part choral piece for a small group, usually upon religious themes, and often unaccompanied by any instrumentation. Bach’s six known motets take this last point to a fascinating extreme insofar as although his motets have instrumental parts, the vocal writing is so rich and so flush against the accompaniment – organ or small chamber group – that even with a small chorus you have to listen with a great deal of concentration to be certain that there are any instruments playing under it at all. Accordingly, they are the most hermetic of this avowed Lutheran’s works – maybe not as conceptually taut as Art of the Fugue, but immeasurably more beautiful. This is the longest motet of the six, which are my favorites of Bach’s catalogue of extant works which number well over 1000. The title translates to “Jesus, My Joy” and the text is divided between Chapter 8 of Paul’s epistle to the Romans and verse by one Johann Frank: “Defiance to the old dragon, defiance to the vengeance of death, defiance to fear as well! Rage, world, and attack; I stand here and sing in entirely secure peace!”

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

138. Spacelab

Kraftwerk: The Man·Machine (Kling Klang/EMI, 1978);

composed by Ralf Hütter & Karl Bartos

My favorite story about Kraftwerk is Tina Weymouth’s anecdote about meeting Ralf Hütter and trying to break the ice by complimenting Kraftwerk’s lyrics, only to have him snap, “What?! The lyrics are stupid!” This self-assessment is basically accurate, but Kraftwerk’s lyrics are a very peculiar kind of stupid – as is this group’s overall aesthetic of human beings looking and behaving as much like automatons as possible and playing what they conceptualize as music that only machines would enjoy let alone make. The irony is that once they abandoned what they had in common with other motorik German groups that favored repetition like Neu! (an early Kraftwerk offshoot) and turning their mechanized sound and imagery into a Constructivist cartoon, they started making very singular and strangely emotional pop music out of it. This track has no lyrics other than the title, repeated through a vocoder, interspersed with a melancholy Schubertian theme, against the same kind of synthesized bottom that activated Giorgio Moroder’s production of Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love,” but harder, more angular, and more unrelenting. The resulting effect is strangely soft and beautiful, just as contemporary extruded disco mixes began opening up emotional territory that songs themselves could not touch.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

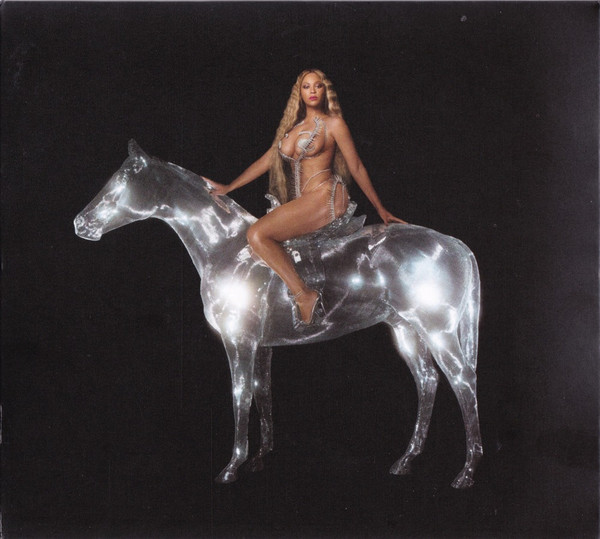

137. Plastic Off The Sofa

Beyoncé: Renaissance (Parkwood Entertainment/Columbia, 2022);

composed by Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter, Sydney Bennett, Sabrina Claudio, Nick Green, and Patrick Paige II

I was a late adopter of Beyoncé, basically because the first decade or so of her busterblocking post-Destiny’s Child career seemed so obvious. I liked “Crazy In Love” fine, loathed “Halo” much, and felt mostly uninvolved with all of it. The kind of Big Pop with a half dozen composer credits per track has no intrinsic need for me to like it, shall we say, so its pleasures tend to hit me in an unscheduled way. Consequently, half the planet already knew that Beyoncé in 2014 was a massive reinvention years before I listened hard and figured it was not only more a reinvention of the whole concept of reinvention, but also that reinvention was a feat that each of the three epochal albums that have followed since have managed in turn. Two of this track’s five co-composers were key members of The Internet, an under-sung offshoot of the long-gone Odd Future collective. Together, these weirdos craft a side-winding evocation of sex that unapologetically stains the upholstery: “I know you can't help but to be yourself 'round me . . . And I know nobody's perfect, so I'll let you be.” I could be wrong, but that sounds like Jay-Z to me.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

136. Ich Habe Gelernt (I Have Learned)

Lotte Lenya & Heinz Sauerbaum with Wilhelm Brückner-Rüggeberg, cond.: Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Columbia, 1956);

composed by Kurt Weill & Bertolt Brecht

This 1930 opera – a fable about an imagined (and geographically confused) American city where the only punishable offense is not being able to pay your bills – was the last project Weill and Brecht did together before Weill bridled at Brecht’s much-harder-left politics and went his own way – and very shortly before both of them had to run for it upon the advent of the Austrian corporal. Not nearly as well-known as Threepenny Opera, it shows the strain of having been expanded from a shorter piece (the Mahagonny-Songspiel). To my ears, the expansion resulted in a comparatively draggy second half, but the first half is a treasure house. The best-known number is the “Alabama-Song” (covered by the Doors), but the prize is this brief anomalous duet between a prostitute and the hapless protagonist Jimmy. After haggling over the fee, she says, “I have learned, whenever I meet a man, to ask him what he is used to. Therefore tell me how you would like me to be.” Accompanied by a solo saxophone playing one of the most melancholy melodies ever written, he tells her. When asked about her wishes, she replies, “It is perhaps too soon to talk of them.”

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Saturday, December 20, 2025

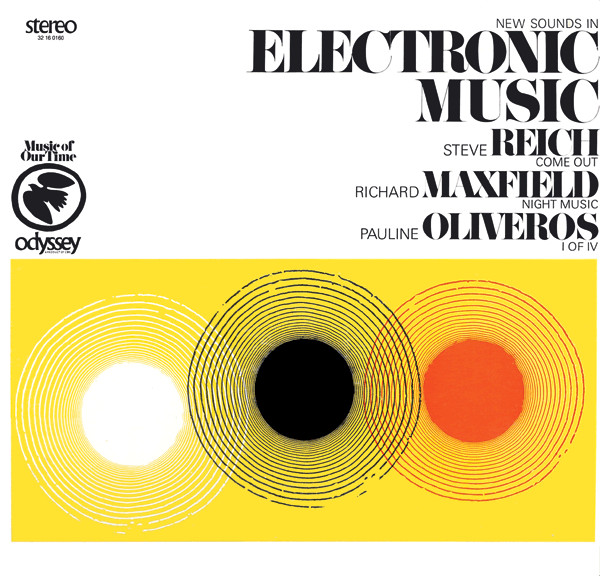

135. Come Out

Steve Reich / Richard Maxfield / Pauline Oliveros: New Sounds In Electronic Music (Columbia/Odyssey, 1967);

composed by Steve Reich

Composers that get called “minimalist” really hate that term – I once saw Philip Glass shut a questioner down just for using the word – because it is not relevant to their actual objective, which is to use whatever means are most appropriate to bringing out qualities that other musical forms and strategies do not. A lot of it may sound merely repetitious to some, but if you bring full attention to it, you acquire a kind of third (and fourth) ear that zeroes in on the interstitial information that tumbles sideways out of the music. This early piece by Steve Reich is kind of an acid test for that idea, in multiple senses of the term. A fragment from a taped interview with a gentle-voiced victim of a police beating relating how he had obtained medical treatment by making one of his bruises bleed again – to “come out to show them” – which phrase is repeated on multiple tape loops in tandem which gradually – and then rapidly – go out of phase with each other, until the overlapping vocals sound like engines or hundreds of beating wings. It also turns the phrase into a political wake up you can feel in your bones.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Friday, December 19, 2025

134. Moisture

The Residents: Commercial Album (Ralph, 1980);

composed by ? ? ? ?

The Residents acquired their avant-ish cachet as much for their Pynchonesque refusal to identify their individual members as for their music which usefully served to deflect attention from both. The music was still the point, but the genial hostility of the presentation – their “management” gave interviews speaking about the group in the third person in voices nonetheless recognizable from the records – gave the musical usages a little more breathing room than they might otherwise have. Others may disagree about their later theatrical incarnations, but I think this album was their apotheosis, conceptually: an album of forty tracks each lasting exactly one minute, yet each making an impression. None have much of a beat; most of the instrumentation is rudimentary synths with voices mewing microtonal melodies almost-tonal-but-not on top. The effect is not so much distortion as decay: as if this technologically oriented music had been fashioned from biomatter that was audibly decomposing - as if DEVO were Weird Al Yankovic. On this emblematic track, two verses are separated by a jazzish Fred Frith guitar solo. In the first, a “stranger” is observed perspiring a lot. In the second, they find a snail in her purse after she dies. Time passes.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Thursday, December 18, 2025

133. God, What Am I Doing Here?

The Holy Modal Rounders: Last Round (Adelphi, 1978);

composed by Barbara Ann Goldblatt

I do not mean to be insulting, but I suspect that this song may be perfect, if you can imagine the Absolute having multiple flavors and toppings. Its author, who answered to Antonia, occasionally adding Duren or Stampfel to it, was one of the primary songwriters for a group she made possible by introducing its two original members to each other. Whether she was a performing member of the group herself would have to be confirmed by eyewitnesses, because it is not entirely clear from the extant but strangely evanescent recordings. She wrote the song that came nearest to being a hit – “Bird Song” – when it was included on the Easy Rider soundtrack. She also wrote “Fucking Sailors In Chinatown,” which did not appear on record until this century. And she also-also wrote the single greatest songful meditation on human existence in the language (since Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps has no words and would be in French anyway): “The cold wind from space / Is blowing in my face. / God, what am I doing here?” The question is both a cosmic conundrum and a sputter of exasperation, like Bette Davis saying, “What a dump!” in Beyond the Forest.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)