Sunday, December 24, 2023

25. Opening Medley (Sleigh Ride, Make Yourself Comfortable, Creep, Dancing Queen, You Have Placed A Chill In My Heart, Oh Happy Day, We Wish You a Merry Christmas)

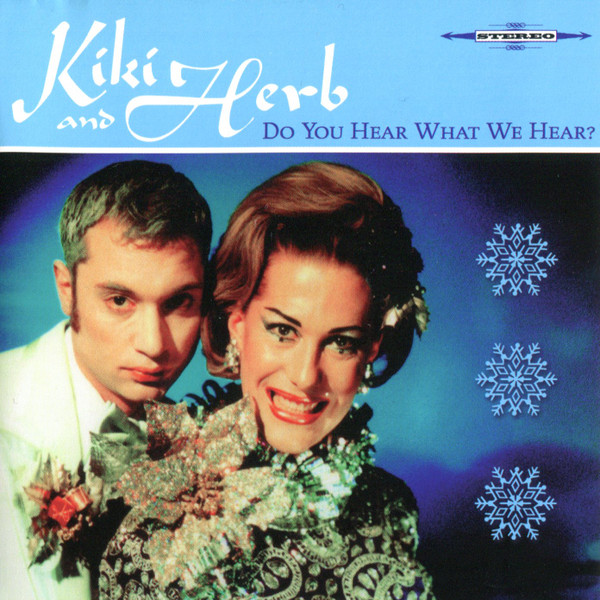

Kiki & Herb: Do You Hear What We Hear? (People Die, 2000);

various composers; arranged by Justin Vivian Bond and Kenneth Melman

“Mary of Nazareth? We have your test results!” I have always maintained that this is the most theologically sound of Xmas medleys, and I have it on reasonable if second-hand authority that both Kiki and Herb agree with me. How many other holiday garlands include that tough love aphorism from John 3:16 about Him giving His only begotten son so that all who believeth in Him shall have everlasting you know what? None with which I am familiar, and I intend to keep it that way, because in any other similarly quasi-pagan context it could be a bummer, notwithstanding that it does constitute what the word “Gospel” means and references: the Good News, as such. In Kiki & Herb’s context, it is tough love, but “tough” as in “chewy.” And they follow it with the 23rd Psalm and make it sound like a whole lot of nosh before thine enemies. “So, make yourself comfortable, baby. Baby who? Baby Jesus!” And you slow walk that figgy pudding to these carolers at your peril, not least because they open with approaching sleigh bells accompanied by screams of helpless terror. The record changer is automatic, and we won’t go until we get some.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (on average) during Advent.

24. Ooh Poo Pah Doo, Parts 1 & 2

Jessie Hill (Minit 607, 1960);

composed by Jessie Hill

I love a manifesto that knows what it is about, which is that some of the most resonant harbingers come after the fact as well as before it, because the fact is mostly irrelevant. This great Allen Toussaint production begins with an a capella Mardi Gras Indian style call and response before the beat drops and the auteur promises to tell us all about “Ooh Poo Pah Doo.” And then he tells us nothing about it, as such, except to repeat in numerous variations, precisely this: “Baby, don't you know they call me the most? / And I won't stop tryin' till I create disturbance in your mind.” And that disturbance is what happens. Is there any “what” here, or just a “how”? Are there nouns, or just gerunds – incognito verbs posing as fixed entities? Is anything “fixed”? Dick Hebdige once made a delightful point about the Sex Pistols in his book Subculture: that “Holidays In The Sun” was both about semantic disorder and a prime example of it. Maybe it was, but this was more to the point. Part 2 is not the other half of a long performance cut in two: it is exactly the same, except completely different.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

23. Two Steps Back

The Fall: Live At The Witch Trials (Step-Forward, 1979);

composed by Mark E. Smith and Martin Bramah

The Fall was the quintessential postpunk entity insofar as they postdated whatever punk was by a margin delineated entirely by Mark E. Smith’s willingness to expel breath as well as draw it, although his consonants did get dodgy in later years. More miraculous is that while the quality of the music he extracted from the many Falls always fluctuated by definition, it never declined like some fookin’ legacy act. So one’s personal mileage will differ. This track by the earliest edition is one of the more Deutscherok influenced – dark, hypnotic guitar and cheap electric piano patterns anchored by Karl Burns’s drums (the Fall, like Roxy Music with Paul Thompson, had a knack for never being without powerful and well-miked drummers), with Smith on top sprechstimming about various hallucinogenic experiences which this bunch was fonder of than many of their erstwhile contemporaries. But this is also one of the only Fall tunes that is not only fractious, it is also frankly melancholy without being cautionary. The last two verses are about Mark’s psychedelic comrades queuing up for the Dole, lest they be remanded to the “Cracker Factory” – rehab – where they can be re-retro-refitted for “the working routine again.” Two doors down.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Friday, December 22, 2023

22. Home On The Range

Ken Maynard (recorded April 14, 1930 for Columbia Records - unreleased);

composed by Brewster M. Higley and Daniel E. Kelley

Ken Maynard was a popular actor in screen westerns – many silents in the ‘20s, and when sound came in, the quality of his voice allowed him to extend his career another decade. During that transition, he also made his only commercial recordings of cowboy songs – eight total, only two of which were released on a single 78. His recording of this standard from the 1870s only appeared on latter day anthologies. Apart from Maynard’s rather adenoidal delivery being very much in the manner of many very popular singers of western ballads in that time, this version of the tune has a verse that is rarely heard now: “The red man was pressed from this part of the West, / He's likely no more to return / To the banks of Red River where seldom if ever / Their flickering camp-fires burn.” Contrary to the assumption that this verse might have an unpleasant history, a little digging in Wikipedia indicates instead that this verse only appeared in the version collected around 1910 by John Lomax, and likely derived from African American sources. So, a celebration of manifest destiny, or a more darkly bemused report on the actual state of things on the range?

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Thursday, December 21, 2023

21. 3/4 for Piano and Orchestra

Carla Bley (Watt, 1975);

composed by Carla Bley

Carla Bley wrote her only full-on classical piece when, feeling misplaced, she had temporarily “renounced jazz.” Dennis Russell Davies conducted the 1974 Lincoln Center premiere of this piano concerto – entirely in waltz time (thus the title) with a theme reminiscent of Charles Mingus’s “Meditations On Integration,” but not all that much like it. However, Bley had already soured the piece’s future when the Times quoted her comments on the musicians: “When I'm conducting the people I've been playing with for 10 years, ... they add a personal dimension to the music ... but when I got with The Ensemble, I realized I must be a jazz musician because they phrase so differently from the way I do.” The version she recorded the following year puts this dialectic into relief. Featured soloist Ursula Oppens does not improvise, as such – she plays a cadenza. But there is nothing lockstep about the free floating rhythmic feel of the chamber ensemble, which Bley’s signature voicings make seem three times larger than it is, even when down to near-silence, underneath the unbelievably melancholy one-handed figure that anchors from the beginning to the end. Jazz - whatever it is - could not renounce her.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

20. Plástico

Willie Colón & Rubén Blades: Siembra (Fania, 1978);

composed by Rubén Blades

I live for moments when music goes from “This may be an educational example of a style with which I am unfamiliar in a language I do not speak” to “Oh, goody – this one again!” If I knew more about salsa, I might think that being turned onto it via the best-selling album in that genre is like having your entire notion of what rock & roll is delineated by Sgt. Pepper – which is to say, probably misleading but why resist? What I can tell you is that I have never heard a bad Blades album in Spanish, and although he has written even sharper lyrics on some of his subsequent albums with Seis del Solar, the humor and verve of this album is unmistakable. The theme of this lead track – keep it real, Latino unity – is no revelation by itself, but the way Blades’s conversational cadence skips and jibes around Willie Colon’s trombone-heavy groove is like having the Rosetta Stone dig you up. Colon’s earlier albums with Hector Lavoe were plenty epochal – you can hear that, too – but Siembra is even farther from those than they were from El Malo (1967). No wonder both these guys went into politics.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

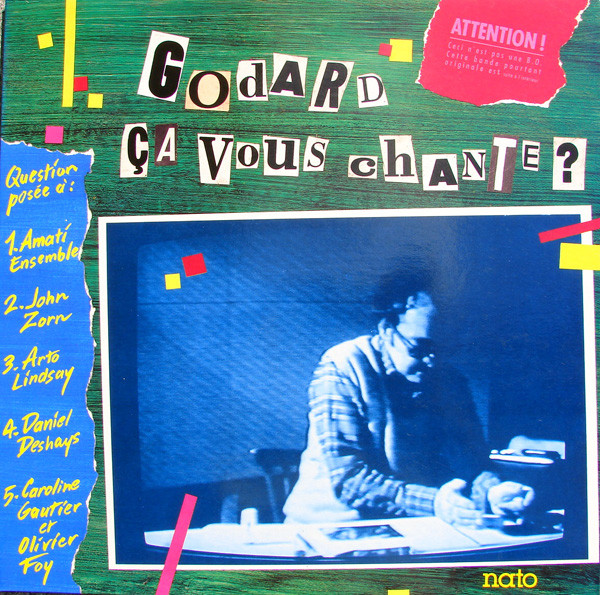

19. Godard

John Zorn (originally on Godard ça vous chante? (VA – Nato, 1986), later reissued on Godard/Spillane (Tzadik, 1999);

composed by John Zorn

A lot of people have notions of “montage” that are no less quaint than the most gemütlich notions of “harmony” – the question being whether these strategies just smooth over natural fissures in the material or rather allow you to hear a lot of disparate bits of information more vividly than you would otherwise? This 18-minute piece John Zorn assembled in 1985 for an obscure multi-artist tribute to Jean-Luc Godard is strangely anomalous in his massive discography as it answers both questions at once. Working from a number of composed sections on randomly assembled index cards, Zorn conducts (while playing and occasionally barking in French) a small group of improvising (and sight-reading) musicians, including Christian Marclay manipulating turntables, one narrator (in Chinese), one narrator/singer (in Japanese), and Richard Foreman reading snatches from Bruno Schultz’s “The Street of Crocodiles” (which here sound a lot like his own plays). Bursts of noise and deliberately jarring exclamations notwithstanding, it is the prettiest as well as the most disquieting Zorn piece I have ever heard in a way none of his other (terrific) game pieces are. His estimable and more visible Mickey Spillane tribute a couple of years later could not turn the same trick.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)