Thursday, November 30, 2023

4. Symphony №5 in D minor, Op. 47: First Movement (Moderato)

(Premiered Nov. 21, 1937, with Yevgeny Mravinsky conducting the Symphony Orchestra of the Leningrad State Philharmonic);

composed by Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (1906-1975)

If you know Shostakovich, you probably know this symphony. If you know this symphony, you probably know that Stalin’s positive response to it was the only thing keeping the composer out of the Gulag. He was their best beyond question, and even Stalin apparently thought so. Just that every now and then the apparatchiks made him pule like a whipped dog on cue because too many pointy-heads at liberty have a way of slowing History down, despite bringing the nonpareil socialist flavor. But he was Shostakovich and he puled like he did anything else. In the first movement, the trumpety pageant of inexorable history thunders past, but in the last minute, the strings go almost completely quiet while an unprepossessing secondary theme introduced earlier, is reintroduced as a smiling curse: a lonely solo theme played first by piccolo, then seconded by violin. A pule like disobedient history. Bulgakov had to keep the manuscript of The Master and Maragarita literally buried when he was not writing it, as if his words might run away and denounce their author. Shostakovich had no choice but to put an equivalent insult in plain sight. But he put it where no one dared touch it.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

3. Barangrill

Joni Mitchell: For The Roses (Asylum, 1972);

composed by Joni Mitchell

Asking when Joni Mitchell “peaked” is just stupid, because all that means is when did she peak for you. Talent that humongous just needs to connect, and for me – like many – she connected most on her first eight albums. After Hejira (which I actually find a little windy), she kept connecting, but mostly not. This anomalous tune comes right in the middle of the period when all she had to do – commercially and artistically both – was push, and people are still trying to figure out what hit them. Coming after Blue, her most “confessional” album, For The Roses splits its twelve songs evenly between her piano and guitar and its pronouns between “I” and “you,” except for this picaresque narrative for guitar and woodwinds about people who sound a little desperate, but are, for just seconds at a time, ecstatically happy – about earrings, tires, cocktails, and Nat King Cole. The spare instrumentation sounds almost orchestral wrapped around the cadence of her voice, which obviates any set meter. It is the saddest song about happiness I have ever heard. Her best next move was to find a drummer who could follow her, and we are lucky that it was John Guerin.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Monday, November 27, 2023

2. Little Cow And Calf Is Gonna Die Blues

Skip James (Recorded Feb. 1931; released on Paramount 13085, b/w “How Long 'Buck'”); composed by Nehemiah Curtis James

Somewhat miraculously, all of the just eighteen sides Skip James cut for Paramount in 1931 have survived. On five of them, he played piano rather than the open D minor guitar that still makes the biggest impression on newcomers. Much of the latter impression comes from the way he sang so seductively over his relentlessly lilting guitar figures, in a sinuous falsetto both sorrowful and utterly pitiless, with lyrics to match. What is also unsettling about that voice is the way its seductive character simply vanishes on the piano sides. Arguably, James could not really play the piano – he banged out triads in several different tempos at once and almost distractedly crammed words into the cracks and breathless ha-aha-has. But this other weirder approach not only validates the guitar sides, it also suggests the breadth and depth of James’s overall concept. The effect is less Thelonious Monk than Cy Twombly – a deliberately primitivist approach elucidating a unique information system. The words, the notes, and the cursed feelings are all stones in his passway, piled into cairns leading the way to a hell planet. What happens when a first-order intelligence runs smack into the meanest adversity? Very occasionally, something like this.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

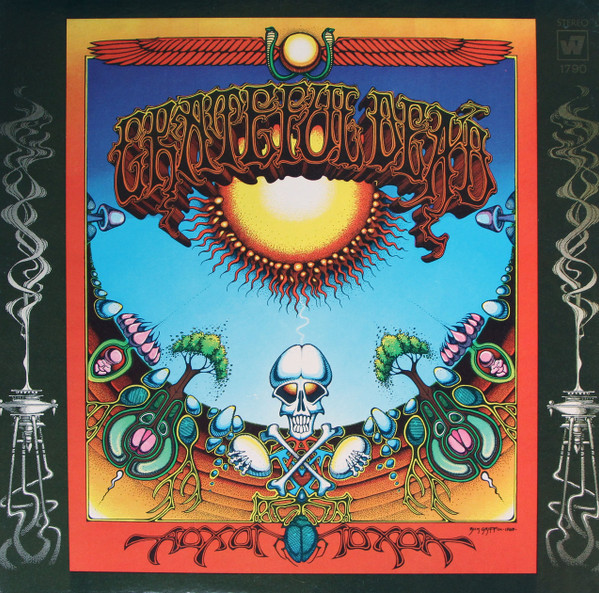

1. “What’s Become of the Baby?”

The Grateful Dead: Aoxomoxoa (Warner Bros., 1969);

composed by Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter

This may be the most alien track from the Dead’s most lysergic album, and I do not know anyone who loves it, let alone plays it often. I do play it, however – both the original and the 1971 remix, and no other track on Aoxomoxoa was so utterly – and mysteriously – transformed. For eight minutes and change, Jerry Garcia sings a Robert Hunter poem about Jesus (I think) through a ring modulator, improvising a melody from a fixed set of pitches. How does it compare to Stockhausen’s “Gesang der Jünglinge,” to pick an utterly non-random example? No idea. Same planet, if not jukebox. But how does it compare to the rest of Aoxomoxoa, not to mention everything else that happened after the Dead stopped going into debt to make albums that sounded like the supernovas in their heads? Well, same jukebox, if not planet. There is a delicacy to Hunter’s lyrics on this album – an air of questing gobsmacked generosity to fragile compatriots that carried over to the more accessible tunes on the subsequent albums that put them well into the black, while permanently confusing their mass audience about the cost of what they had put themselves through to get there.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (approximately) during Advent.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)