Wednesday, November 29, 2023

3. Barangrill

Joni Mitchell: For The Roses (Asylum, 1972);

composed by Joni Mitchell

Asking when Joni Mitchell “peaked” is just stupid, because all that means is when did she peak for you. Talent that humongous just needs to connect, and for me – like many – she connected most on her first eight albums. After Hejira (which I actually find a little windy), she kept connecting, but mostly not. This anomalous tune comes right in the middle of the period when all she had to do – commercially and artistically both – was push, and people are still trying to figure out what hit them. Coming after Blue, her most “confessional” album, For The Roses splits its twelve songs evenly between her piano and guitar and its pronouns between “I” and “you,” except for this picaresque narrative for guitar and woodwinds about people who sound a little desperate, but are, for just seconds at a time, ecstatically happy – about earrings, tires, cocktails, and Nat King Cole. The spare instrumentation sounds almost orchestral wrapped around the cadence of her voice, which obviates any set meter. It is the saddest song about happiness I have ever heard. Her best next move was to find a drummer who could follow her, and we are lucky that it was John Guerin.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Monday, November 27, 2023

2. Little Cow And Calf Is Gonna Die Blues

Skip James (Recorded Feb. 1931; released on Paramount 13085, b/w “How Long 'Buck'”); composed by Nehemiah Curtis James

Somewhat miraculously, all of the just eighteen sides Skip James cut for Paramount in 1931 have survived. On five of them, he played piano rather than the open D minor guitar that still makes the biggest impression on newcomers. Much of the latter impression comes from the way he sang so seductively over his relentlessly lilting guitar figures, in a sinuous falsetto both sorrowful and utterly pitiless, with lyrics to match. What is also unsettling about that voice is the way its seductive character simply vanishes on the piano sides. Arguably, James could not really play the piano – he banged out triads in several different tempos at once and almost distractedly crammed words into the cracks and breathless ha-aha-has. But this other weirder approach not only validates the guitar sides, it also suggests the breadth and depth of James’s overall concept. The effect is less Thelonious Monk than Cy Twombly – a deliberately primitivist approach elucidating a unique information system. The words, the notes, and the cursed feelings are all stones in his passway, piled into cairns leading the way to a hell planet. What happens when a first-order intelligence runs smack into the meanest adversity? Very occasionally, something like this.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

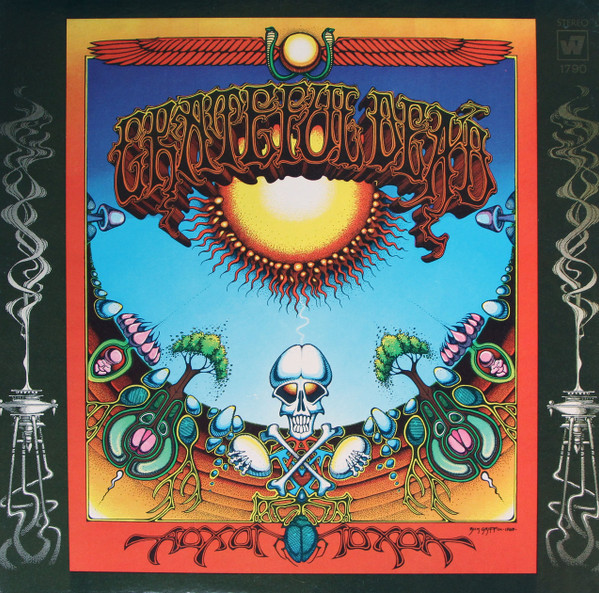

1. “What’s Become of the Baby?”

The Grateful Dead: Aoxomoxoa (Warner Bros., 1969);

composed by Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter

This may be the most alien track from the Dead’s most lysergic album, and I do not know anyone who loves it, let alone plays it often. I do play it, however – both the original and the 1971 remix, and no other track on Aoxomoxoa was so utterly – and mysteriously – transformed. For eight minutes and change, Jerry Garcia sings a Robert Hunter poem about Jesus (I think) through a ring modulator, improvising a melody from a fixed set of pitches. How does it compare to Stockhausen’s “Gesang der Jünglinge,” to pick an utterly non-random example? No idea. Same planet, if not jukebox. But how does it compare to the rest of Aoxomoxoa, not to mention everything else that happened after the Dead stopped going into debt to make albums that sounded like the supernovas in their heads? Well, same jukebox, if not planet. There is a delicacy to Hunter’s lyrics on this album – an air of questing gobsmacked generosity to fragile compatriots that carried over to the more accessible tunes on the subsequent albums that put them well into the black, while permanently confusing their mass audience about the cost of what they had put themselves through to get there.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (approximately) during Advent.

Sunday, December 9, 2012

4. “Singing Aboard Ship (Laivassa lauletaan)”

Composed by Veljo Tormis (1983); as performed on Tõnu Kaljuste/Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir: Veljo Tormis - Litany To Thunder (ECM New Series 1999)

There is music that wishes war away in the subjunctive (“would it were not so”), while other music does not even warn of a hard rain so much as it says the rain it do fall, precisely how it falls, and upon whom. Apart from being an Estonian music student in the 1940s, I cannot imagine what Tormis experienced, but this a capella setting of an Ingrian-Finnish folk song for alto soloist and mixed chorus reminds me more than a bit of Maria Irene Fornes’s The Danube, in which she constructed an entire post-nuclear non-future from a discarded Magyar language record. This is a traditional song of ethnic Finnish women from the Neva river valley singing about and to men who have been impressed into the Russian military, awaiting transport aboard ships anchored offshore. The original song is the women’s lament, but in Tormis’s adaptation, the men answer – in the wordless tightly-harmonized choral mass that underpins the whole, beginning the piece as a low growl that rises to a sardonic roar as it joins with the women ringing over the water: “When the boys sang on the ship, / the girls thought it was an organ playing.”

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent from Dec. 1 through Dec. 25. Or, most likely, later.

Saturday, December 8, 2012

3. “1983 (A Merman I Should Turn To Be)”/“Moon, Turn the Tides…gently, gently away”

The Jimi Hendrix Experience: Electric Ladyland (Reprise, 1968);

composed by Jimi Hendrix

Electric Ladyland is the only album Jimi Hendrix released in his lifetime that was entirely the way he wanted it and it now makes for an unsettling backwards telescope into what might have transpired if the ambulance medics had kept his lungs clear in 1970. Not coincidentally, this sixteen-minute tone poem about the end of the world in the middle of it has to be addressed with a certain skepticism. Not because of the music, of course. Played entirely by Hendrix, except for Mitch Mitchell’s drums and occasional flute interjections by Chris Wood of Traffic, the track comprises stately inversions of one chord extended through a bone-chilling sequence of sound constructions produced entirely through the delicate interaction of upside-down guitar, amplifier, and remarkably little tape manipulation. It remains one of the very finest and intuitively musical noise excursions in the music. So, why skepticism? Because it sounds like an ending when it was not one. Because it also sounds like an experimental opening that did not ultimately open (although his “Machine Gun” solo makes me wonder). Its only message is that Hendrix could do anything he wanted and we live with never knowing exactly what that means.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent from Dec. 1 through Dec. 25. Or, most likely, later.

Sunday, December 2, 2012

2. “Workin’ for MCA”

Lynyrd Skynyrd: Second Helping (Sounds of the South/MCA, 1974);

composed by Ed King & Ronnie Van Zant

Despite how late in the day it (really) is, some people still think I must be joking when I sing this band’s praises, but sing them I do. Skynyrd still messes with certain ironic (or “ironic”) sensibilities because their singular ways of layering contradictory meanings in their songs were so full-impact that they rarely registered as irony at all. Mastermind Ronnie Van Zant was also singular for (among many other things) the miraculous absence of two qualities in his makeup: sentiment and ressentiment. Accordingly, “Workin’ For MCA” is the single best song about record companies ever. Its adversarialism was nothing new, but only Van Zant would threaten the suits with physical violence while simultaneously demystifying their economic relationship so concisely in his title. Absent is any punkista pretension about being artists putting up with corporate parasites. Skynyrd were artists to the max – and no one knew that better than they – but no rock band ever was more aware that it had been given a job and contextualized its hostility in such real world terms. Underlining Van Zant’s concept were six musicians who had mastered their craft by playing for months inside an unventilated metal shack in the Florida heat.

Note: This is the third annual series of 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent from Dec. 1 through Dec. 25. Or so.

Saturday, December 1, 2012

1. “Lucinda”

Randy Newman: 12 Songs (Reprise, 1970);composed by Randy Newman

If Randy Newman’s second and greatest album had a theme, it was not so much alienation as anomie: the breakdown of social bonds between individual and community. 12 Songs posed an unsettling corollary: What if anomie was something you liked? Accordingly, the narrators of these songs are mostly creepy guys at the end of their tethers. “Suzanne” comprises an obscene phone call, for example. In “Lucinda,” a young woman is lying on a beach in her graduation gown at sunset. The narrator lies down beside her, for reasons unstated. Since she never speaks, he only gradually realizes that she is really just there to wait for the beach cleaning truck to come along and scoop her body up with the day’s trash. And it does. After he fails to avert this, the narrator’s dumbstruck explanation is that “She just wouldn’t go no farther.” This recalls my pet theory about why The Night of the Hunter is a truly scary film: because Charles Laughton probably empathized most with the Robert Mitchum character. “Lucinda” reminds me of the town drunk incapacitated by his discovery of Shelley Winters’ bound corpse in the river - an utterly appalling image with few rivals in American cinema.

Note: 25 secular essays (each one exactly 200 words long) about 25 songs, intended to appear one per day during Advent from Dec. 1 through Dec. 25. Or so.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)