Sunday, December 24, 2023

25. Opening Medley (Sleigh Ride, Make Yourself Comfortable, Creep, Dancing Queen, You Have Placed A Chill In My Heart, Oh Happy Day, We Wish You a Merry Christmas)

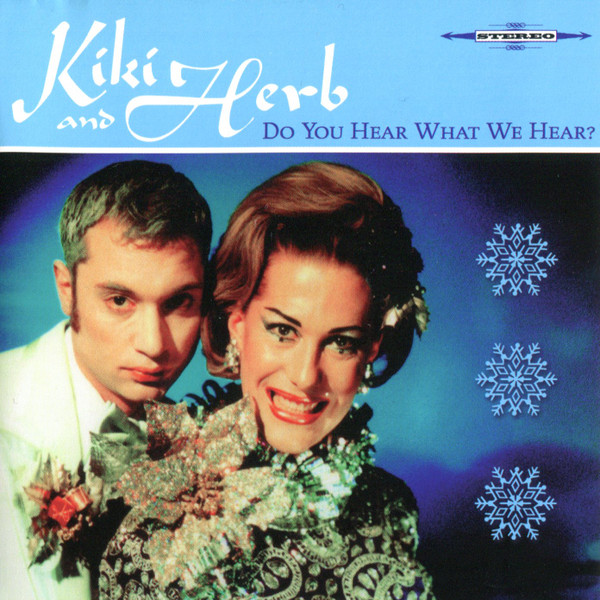

Kiki & Herb: Do You Hear What We Hear? (People Die, 2000);

various composers; arranged by Justin Vivian Bond and Kenneth Melman

“Mary of Nazareth? We have your test results!” I have always maintained that this is the most theologically sound of Xmas medleys, and I have it on reasonable if second-hand authority that both Kiki and Herb agree with me. How many other holiday garlands include that tough love aphorism from John 3:16 about Him giving His only begotten son so that all who believeth in Him shall have everlasting you know what? None with which I am familiar, and I intend to keep it that way, because in any other similarly quasi-pagan context it could be a bummer, notwithstanding that it does constitute what the word “Gospel” means and references: the Good News, as such. In Kiki & Herb’s context, it is tough love, but “tough” as in “chewy.” And they follow it with the 23rd Psalm and make it sound like a whole lot of nosh before thine enemies. “So, make yourself comfortable, baby. Baby who? Baby Jesus!” And you slow walk that figgy pudding to these carolers at your peril, not least because they open with approaching sleigh bells accompanied by screams of helpless terror. The record changer is automatic, and we won’t go until we get some.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (on average) during Advent.

24. Ooh Poo Pah Doo, Parts 1 & 2

Jessie Hill (Minit 607, 1960);

composed by Jessie Hill

I love a manifesto that knows what it is about, which is that some of the most resonant harbingers come after the fact as well as before it, because the fact is mostly irrelevant. This great Allen Toussaint production begins with an a capella Mardi Gras Indian style call and response before the beat drops and the auteur promises to tell us all about “Ooh Poo Pah Doo.” And then he tells us nothing about it, as such, except to repeat in numerous variations, precisely this: “Baby, don't you know they call me the most? / And I won't stop tryin' till I create disturbance in your mind.” And that disturbance is what happens. Is there any “what” here, or just a “how”? Are there nouns, or just gerunds – incognito verbs posing as fixed entities? Is anything “fixed”? Dick Hebdige once made a delightful point about the Sex Pistols in his book Subculture: that “Holidays In The Sun” was both about semantic disorder and a prime example of it. Maybe it was, but this was more to the point. Part 2 is not the other half of a long performance cut in two: it is exactly the same, except completely different.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

23. Two Steps Back

The Fall: Live At The Witch Trials (Step-Forward, 1979);

composed by Mark E. Smith and Martin Bramah

The Fall was the quintessential postpunk entity insofar as they postdated whatever punk was by a margin delineated entirely by Mark E. Smith’s willingness to expel breath as well as draw it, although his consonants did get dodgy in later years. More miraculous is that while the quality of the music he extracted from the many Falls always fluctuated by definition, it never declined like some fookin’ legacy act. So one’s personal mileage will differ. This track by the earliest edition is one of the more Deutscherok influenced – dark, hypnotic guitar and cheap electric piano patterns anchored by Karl Burns’s drums (the Fall, like Roxy Music with Paul Thompson, had a knack for never being without powerful and well-miked drummers), with Smith on top sprechstimming about various hallucinogenic experiences which this bunch was fonder of than many of their erstwhile contemporaries. But this is also one of the only Fall tunes that is not only fractious, it is also frankly melancholy without being cautionary. The last two verses are about Mark’s psychedelic comrades queuing up for the Dole, lest they be remanded to the “Cracker Factory” – rehab – where they can be re-retro-refitted for “the working routine again.” Two doors down.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Friday, December 22, 2023

22. Home On The Range

Ken Maynard (recorded April 14, 1930 for Columbia Records - unreleased);

composed by Brewster M. Higley and Daniel E. Kelley

Ken Maynard was a popular actor in screen westerns – many silents in the ‘20s, and when sound came in, the quality of his voice allowed him to extend his career another decade. During that transition, he also made his only commercial recordings of cowboy songs – eight total, only two of which were released on a single 78. His recording of this standard from the 1870s only appeared on latter day anthologies. Apart from Maynard’s rather adenoidal delivery being very much in the manner of many very popular singers of western ballads in that time, this version of the tune has a verse that is rarely heard now: “The red man was pressed from this part of the West, / He's likely no more to return / To the banks of Red River where seldom if ever / Their flickering camp-fires burn.” Contrary to the assumption that this verse might have an unpleasant history, a little digging in Wikipedia indicates instead that this verse only appeared in the version collected around 1910 by John Lomax, and likely derived from African American sources. So, a celebration of manifest destiny, or a more darkly bemused report on the actual state of things on the range?

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Thursday, December 21, 2023

21. 3/4 for Piano and Orchestra

Carla Bley (Watt, 1975);

composed by Carla Bley

Carla Bley wrote her only full-on classical piece when, feeling misplaced, she had temporarily “renounced jazz.” Dennis Russell Davies conducted the 1974 Lincoln Center premiere of this piano concerto – entirely in waltz time (thus the title) with a theme reminiscent of Charles Mingus’s “Meditations On Integration,” but not all that much like it. However, Bley had already soured the piece’s future when the Times quoted her comments on the musicians: “When I'm conducting the people I've been playing with for 10 years, ... they add a personal dimension to the music ... but when I got with The Ensemble, I realized I must be a jazz musician because they phrase so differently from the way I do.” The version she recorded the following year puts this dialectic into relief. Featured soloist Ursula Oppens does not improvise, as such – she plays a cadenza. But there is nothing lockstep about the free floating rhythmic feel of the chamber ensemble, which Bley’s signature voicings make seem three times larger than it is, even when down to near-silence, underneath the unbelievably melancholy one-handed figure that anchors from the beginning to the end. Jazz - whatever it is - could not renounce her.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

20. Plástico

Willie Colón & Rubén Blades: Siembra (Fania, 1978);

composed by Rubén Blades

I live for moments when music goes from “This may be an educational example of a style with which I am unfamiliar in a language I do not speak” to “Oh, goody – this one again!” If I knew more about salsa, I might think that being turned onto it via the best-selling album in that genre is like having your entire notion of what rock & roll is delineated by Sgt. Pepper – which is to say, probably misleading but why resist? What I can tell you is that I have never heard a bad Blades album in Spanish, and although he has written even sharper lyrics on some of his subsequent albums with Seis del Solar, the humor and verve of this album is unmistakable. The theme of this lead track – keep it real, Latino unity – is no revelation by itself, but the way Blades’s conversational cadence skips and jibes around Willie Colon’s trombone-heavy groove is like having the Rosetta Stone dig you up. Colon’s earlier albums with Hector Lavoe were plenty epochal – you can hear that, too – but Siembra is even farther from those than they were from El Malo (1967). No wonder both these guys went into politics.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

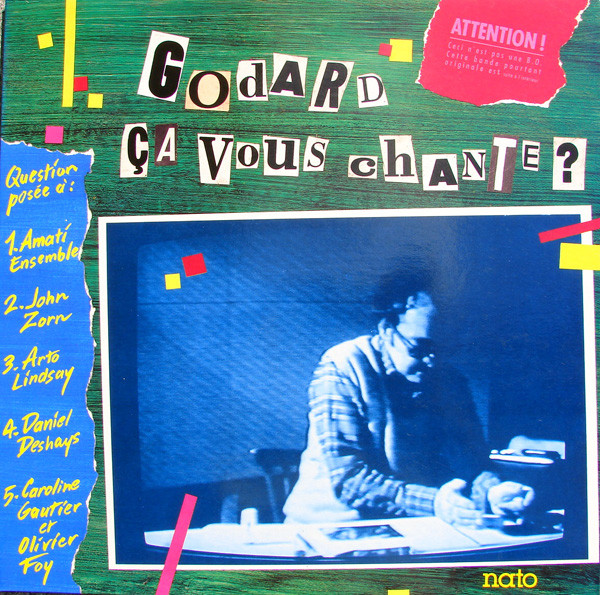

19. Godard

John Zorn (originally on Godard ça vous chante? (VA – Nato, 1986), later reissued on Godard/Spillane (Tzadik, 1999);

composed by John Zorn

A lot of people have notions of “montage” that are no less quaint than the most gemütlich notions of “harmony” – the question being whether these strategies just smooth over natural fissures in the material or rather allow you to hear a lot of disparate bits of information more vividly than you would otherwise? This 18-minute piece John Zorn assembled in 1985 for an obscure multi-artist tribute to Jean-Luc Godard is strangely anomalous in his massive discography as it answers both questions at once. Working from a number of composed sections on randomly assembled index cards, Zorn conducts (while playing and occasionally barking in French) a small group of improvising (and sight-reading) musicians, including Christian Marclay manipulating turntables, one narrator (in Chinese), one narrator/singer (in Japanese), and Richard Foreman reading snatches from Bruno Schultz’s “The Street of Crocodiles” (which here sound a lot like his own plays). Bursts of noise and deliberately jarring exclamations notwithstanding, it is the prettiest as well as the most disquieting Zorn piece I have ever heard in a way none of his other (terrific) game pieces are. His estimable and more visible Mickey Spillane tribute a couple of years later could not turn the same trick.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Tuesday, December 19, 2023

18. Africa Mokili Mobimba

Kale-Roger & Rochereau with L’African Jazz (Surboum African Jazz AJ 70, b/w “Titi”, 1961);

composed by Charles “Déchaud” Mwamba

In the ‘70s, unless the odd Fela Kuti or Manu Dibango disc happened to catch your ear, this may have been the first Afropop that a curious western listener like you or I might hear, as it was the lead cut on John Storm Roberts’s Africa Dances anthology, first released in 1973. It would stand out in any context, however, not just because it is a prime example of the Congolese rumba style as it began to evolve into soukous (and influence a lot other musical forms all over Africa), but a kind of pop explosion in its own right, coinciding with the brief period between Congo’s independence from Belgium and the catastrophes of Lumumba’s assassination, civil war, and Mobutu’s ascension as the quintessential western klepto-client. Recorded in Brussels, intriguingly, but with a lyric in Lingala, ostensibly about “African jazz” taking over the world, but what it sounds like is a paean to Africa itself bursting into some kind of flower. You can imagine it twanging its way out of every radio for miles around you, believing that nothing could stop the feeling it evokes. Political? I suspect that would be difficult to discern even if one spoke the language.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Monday, December 18, 2023

17. Orange Was The Color of Her Dress, Then Blue Silk

Charles Mingus: Changes Two (Atlantic, 1975);

composed by Charles Mingus

Mingus liked the same kind of perfection that Kurt Weill did, which is only to say that if their melody lines were chained molecules, they would have had the same side effects. There are numerous live recordings of this composition that predate the studio version he did with his last great – and maybe greatest ever – small group. If you know the tune, you tend to recognize it the same way you recognize “Sophisticated Lady,” which is also the way someone might have seduced you by the way they lit a cigarette when that was an information-bearing gesture. An ascending line is countered by a reciprocal descending line until they entangle each other, leading to an Eb6-Emaj7-Eb6 triplet that turns the light on, and then sets up yet another new and similar syllogism, and another, into a structure of endless vaults and atria. Mingus never cared much for free playing, per se, but he unquestionably knew how to get rich and elaborate structures out of players who knew how to do it. Don Pullen and George Adams transform the deep folds and rifts of Mingus’s logic engine into a casbah: a bazaar inside an exterior that could not possibly contain it.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Sunday, December 17, 2023

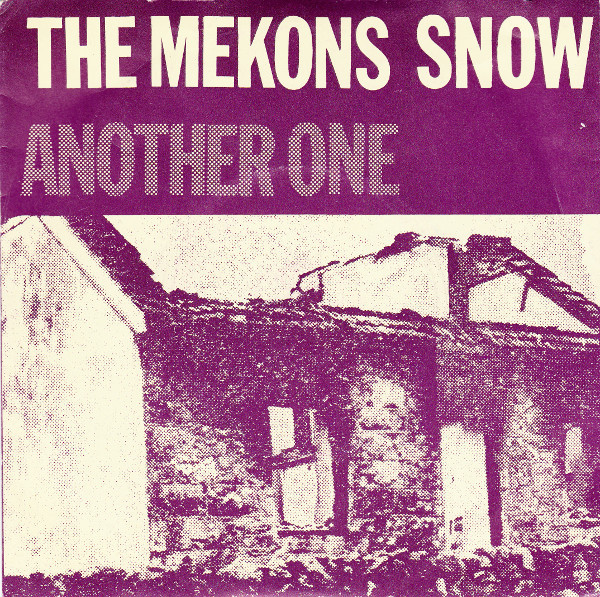

16. Another One

The Mekons (B-side of “Snow” single – Red Rhino, 1980);

composed by Andy Corrigan, Tom Greenhalgh, Mary Jenner, Jon Langford, Kevin Lycett, and Mark White

Before Tom Greenhalgh and Jon Langford revived the moniker for the mordant anarchist collective that is still scratching its own head to this day, the Mekons were a band that epitomized my secret theory of postpunk: punk itself never really existed or happened – and there is no music that truly belongs in that category and no other – because punk was really just a theorized gravitational mega-collapse to which a lot of clever people pretended to react. Postpunk was all there was. The Mekons’ first two singles were like voicemails you could never bring yourself to erase. On the strength of the cult following they attracted, Mekons made an album for Virgin with a cover depicting a chimpanzee not quite typing The Merchant of Venice, and audio to match. This song is from a single comprising the opening and closing tracks of what was ostensibly their second album – vestigially released as The Mekons in 1980 and reissued under various nonsense titles since. This closer is dub taken to absolutes – overdriven bass, echoing guitar lines, and narcoleptic drums, and an even more echoey lyrics about a fracturing romance (maybe) and an old man down the street apparently dreaming the whole thing up.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Friday, December 15, 2023

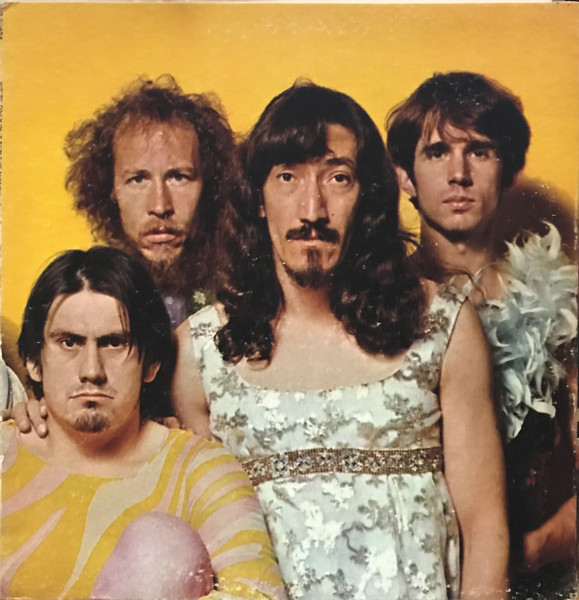

15. The Chrome Plated Megaphone of Destiny

The Mothers of Invention: We’re Only In It For The Money (Verve, 1968); composed by Frank Zappa

This musique concrète interlude concludes Frank Zappa’s parody of Sgt. Pepper and the exploitation of hippie culture in much the same way that “A Day In The Life” did the Beatles’ original a year earlier. Despite a couple of poorly aged sexist jibes, Zappa’s album is still very funny, but without ever dropping its satiric tone most of it is deadly serious. Zappa was especially scabrous about middle class kids blithely sampling mass bohemia like TV dinner entrées, because bohemia was not an abstraction to him – it took brains and willingness to face the very real risk of full-on repression that he saw coming as readily as the WWII internment camps (something he makes explicit in the sleeve notes). So what makes this album more or less unique in Zappa’s catalogue is naked empathy. The paranoid mania for ultra-controlled situations that tended to constrict much of what Zappa did for the next twenty-plus years was strangely absent here, and despite its hyper-meticulous second-by-second construction, the music on this album reflects that. So instead of ending with a majestic reverberating piano chord that eerily trails off into the sunset, this track starts with one that just oozes and throbs at you.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Monday, December 11, 2023

14. Sonic Destroyer

X-101: X-101 (Underground Resistance, 1991);

composer(s) uncredited, but includes “Mad” Mike Banks

One of the things I like most about techno is that its second Detroit iteration gave rise to the obsessives of the Underground Resistance collective. Except for Christian Marclay, no one took the idea of vinyl discs as fetish objects farther, and none farther than this twelve-inch. The B side has one track cut into a groove running from the center of the disc to the edge. The A side – which has no take-up grooves at all – comprises two tracks lasting less than a minute each purporting to be waveform tests, followed by a five-minute four-on-the-floor whomper called “Sonic Destroyer.” Techno is distinguished from other electronic forms sprouting in the mid 1980s, like house, in its dispensing with vocals, or anything that might give its creations any human-scale reference points. This served to give even its most minimal and abstract compositions – often very inexpensively assembled, with cheap electronic gadgets – an alarming “there-ness.” They became facts, the same way certain words – like “I accept your offer” or “This theater is on fire!” – can be legal acts. The hook refrain of “Sonic Destroyer” is what sounds like a Roland 303 imitating a swarm of furious bees. Dance to it? You already did.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Sunday, December 10, 2023

13. Thermador

Butthole Surfers: Tejass – Live In Pepperland 1996 (bootleg);

composed by Gibson Haynes, Paul Leary, and Jeffrey Coffey

Before what lead guy Gibby termed “sgurd” got the better of them (or him), the Butthole Surfers had their first real hit with their second major label album, Electric Larryland. Yet aside from the kind of production budget a major label can (sometimes) afford you (and impoverish you later), their Capitol product differs from their prior output mostly in terms of relative quality control – something of a mixed blessing with this band. The fact being I own every one of their studio albums because so much of what they recorded sounds like a lot of dicking around, obvious borrowing, and druggy hooting, but somehow, on at least one cut per album, they do not simply discover fire, they invent it, and it directly follows from this very scattershot methodology. It is as if they could make their own primordial soup - a rude biomass that could suddenly spew forth something weirdly complete but counter-intuitive, like a chainsaw-wielding soul-stealing accountant, or this track which seems so obvious for them: “Everybody knows freedom, you find it inside your head / Everybody knows Jesus, you’ll meet him when you are dead.” The original rocks. On this bootleg, however, Paul Leary’s guitar has your baby.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Saturday, December 9, 2023

12. P[ussy] Control

Oƪ+>: The Gold Experience (Warner Bros./NPG, 1995);

composed by Prince Rogers Nelson

It may have been the obscenity of Prince’s death from opioids that finally converted me into a sworn anti-reductionist, because I think the very second he was gone, absolutely everything he had ever done sounded like completely different music to me, not least because there could now never be enough of it no matter how jam packed his vault was. Notwithstanding the virtues of concision, the assumption that everything worth saying can be reduced to some essential “point” just fills your life with old herrings, and I would say that goes double for President Purple if that did not restrict the relevant multiple to real numbers. Thus, my abiding love for this song does not arise from it representing anything about its maker; it is more that the pitched orgasmic “Ahhh!!!” tethered to the atonal scale around which Prince structures its refrain resembles the parts of the elephant that stump all five of the proverbial blind taxonomists feeling it up for clues. “Are you ready?” Probably not. The universe of pitched and unpitched sound was to him what your mother’s voice is to you. He could not have converted me to the Jehovah’s Witnesses, but every dinghy needs an oarlock.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Friday, December 8, 2023

11. Looking For a Kiss

New York Dolls: New York Dolls (Mercury, 1973);

composed by David Johansen

This song’s spoken intro is a direct cop from the Shangri-Las’ “Great Big Kiss” – “When I say I’m in love, you best believe I’m in love – L – U – V” – but where that lesser follow-up to “Leader of the Pack” is about one more no-future boyfriend whose attraction affords no explanation, the Dolls offer something weirder: a capsule poetics of FUN. Not just indiscriminate pleasure, but pleasure as a knowledge system with a fearsome overhead cost – one that takes dedication: “You know I can't be wastin’ time / Cause I gotta get my fun.” But colleagues are self-destructing at every turn: “Everyone’s goin’ to your house to shoot up in your room / Most of them are beautiful, but so obsessed with gloom.” It does not mean anything that the only Doll alive today is the one who wrote this manifesto, who “didn’t come here, lookin for no FIX,” but it speaks to what David Johansen had to say in 1973: I want everything this lonely planet has to offer and I will share it with you, but if you die on me, you might fuck everything up. P.S. You will fuck everything up. “You know it’s bad, but you know it’s TRUE.”

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Thursday, December 7, 2023

10. Kassie Jones, Parts 1 & 2

Furry Lewis (Recorded Aug. 28, 1928; released on Victor 21664);

composed by Walter E. Lewis

On April 30, 1900, John Luther "Casey" Jones, a railroad engineer already well known for obsessive punctuality, was trying to brake the passenger train he was driving when it nonetheless even more famously collided with a standing freight. He was the only fatality; his fireman lived. Numerous popular songs about this event began appearing within a few years of it, but this well-known country blues is not really one of them – being more about sex – and it is in two parts for the same reason that Waiting For Godot is – because Godot is not “nothing happening twice,” it’s about Vladimir betraying Estragon. At the end of Act II, Vladimir says, “Tell him you saw me,” instead of “saw us” as he does in Act I. In Part 1, Casey speeds his train while his wife beds a bootlegger running from the police and dreams of her sewing machine needle breaking. In Part 2, she baffles their grieving children by just drawing his pension and moving on as Casey leaves the world after entering something of a dream state, delineated in the opening verse: “Casey looked at his water, water was low / Looked at his watch, his watch was slow.”

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Tuesday, December 5, 2023

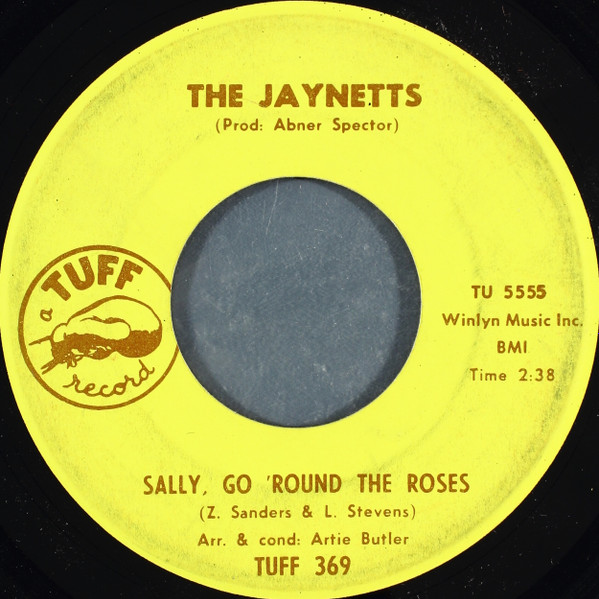

9. Sally, Go 'Round the Roses

The Jaynetts (Recorded 1963; released on Tuff 369, b/w “Instrumental Background To Sally, Go 'Round The Roses”);

composed by Lona Stevens & Zell Sanders

Arguably, this one hit single inspired much of what people now think of as “the Sixties.” Ostensibly a “girl group classic” – as if that made it a trifle by definition – it influenced just about everyone with any kind of mystic bent. It blew teenage Neil Young’s mind. Grace Slick did it pre-Airplane. Pentangle covered it on an album of old folksongs. Can turned it into “Yoo Doo Right” on their neuer-deutscher-rock debut. Donna Summer covered it when she was still Donna Gaines. So what is it? Basically, a drone – just one chord with a quiet but tense jazzy vamp – as an untold number of overdubbed female voices weave around the chord, incantorily warning the title heroine not to “go downtown” lest she encounter “the saddest thing in the whole wide world . . . to see your baby with another girl,” evidently unleashing evil spirits. It went to No. 2, but the recording cost far too much for even the record honchos to get paid (right away, that is) - the hired producer had gone on an obsessive tear – adding the voice of every woman who came near the studio to the mix, while always keeping the sound strangely uncluttered.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Monday, December 4, 2023

8. Drugs

Talking Heads: Fear of Music (Sire, 1979);

composed by David Byrne & Brian Eno

My unpopular theory about Talking Heads is that everything they did after the breakdown of their working relationship with Brian Eno in 1981 was just recontextualization and amplification of things that had already happened. David Byrne reportedly tried to leave after Fear of Music, and in a sense, he did leave – Fear is the last album on which the quartet manifested as a coherent self-contained sound concept, although the (great) joke is that they needed Eno to make it work. The difference between the spare audio verisimilitude of the debut and the seductively disorienting reassembly of the same working parts on the follow-up is one proof of concept. Another is how they and Eno turned a jangly nonentity Byrne wrote in 1978, called “Electricity,” into “Drugs,” in 1979. On old bootlegs, “Electricity” is just the first verse with no chord change or actual tension. “Drugs” instead starts with a recording of Australian birds, leading into a murky shuffle that sounds like the Fatback Band played at 16 rpm. Byrne gasps knowingly silly received crap about drug experiences, punctuated by a creeped out electronic refrain and a loud guitar coda far more “intense” than whatever is being described could possibly be.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Sunday, December 3, 2023

7. Autumn In New York

Composed by Vernon Duke (né Vladimir Dukelsky) in 1934

This song’s counterpart – if not doppelganger – is Duke’s “April In Paris,” which appeared two years earlier in his musical, Walk A Little Faster, with lyrics by E.Y. “Yip” Harburg. In contrast, “Autumn In New York” is in Duke’s own words, and although it ended up in someone else’s show, I suspect he wrote it for reasons of his own. English was his second language and the strain shows – what, if anything, “spells the thrill of first-nighting”? – but the song articulates a strange beauty about New York more difficult to put across than Parisian spring. A lot of it has to do with how the fragmentary words sit on top of Duke’s music, which is like a teaspoon of gravy with ten pounds of flour suspended in it. A musician with élan can lay any number of long and intricate chord modulations into the transitions Duke leaves between verse and chorus and verse – modulations that the emotional shifts in the words and music make necessary. Beboppers created gravitational singularities with the tune – Bird, Powell, and Monk for starters. Duke knew it was redundant to “sigh for exotic lands” if this one makes you feel you are home, steel canyons and all.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Saturday, December 2, 2023

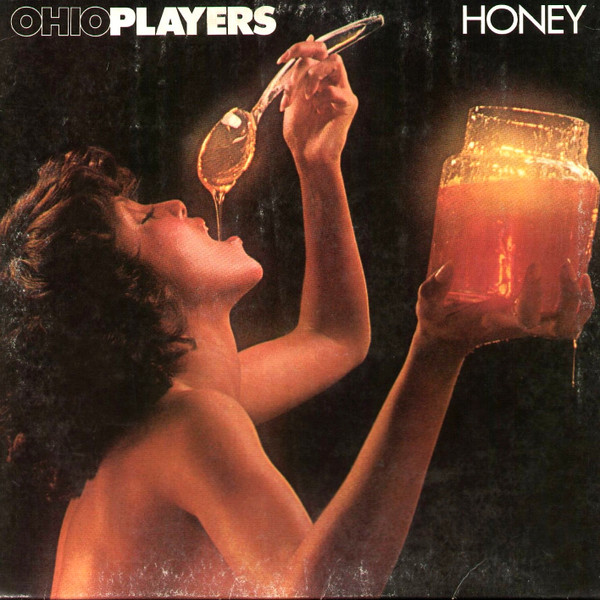

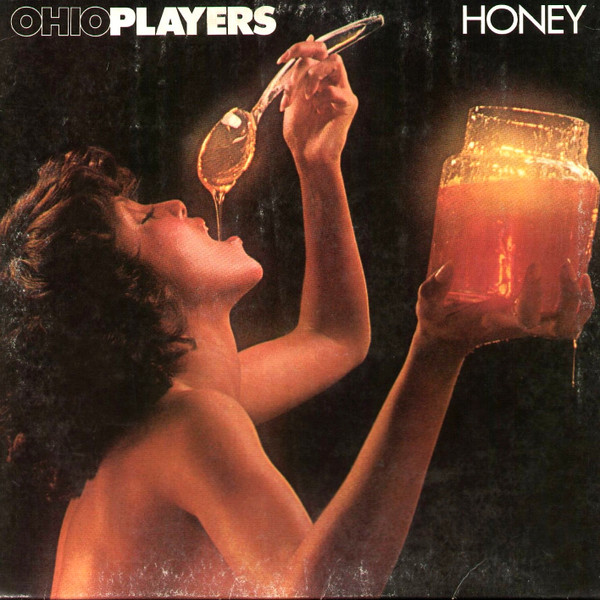

6. Love Rollercoaster

Ohio Players: Honey (Mercury, 1975);

composed by William Beck, Clarence Satchell, James Williams, Leroy Bonner, Marshall Jones, Marvin Pierce, and Ralph Middlebrooks

I hate even mentioning the stupid old rumor that “you could hear someone being murdered” on this track, since the audible “scream” is obviously just someone aspirating a little too close to a hot mike. On the other hand, the single edit is two full minutes shorter than the album track and they kept the scream in both. Even better is that the rumor is nowhere near the most unsettling aspect of the song. The Players largely composed their music in the studio, and by the mid ‘70s after ten or more years of endless gigging, personnel shuffles, and false starts, they had it down and hits they came. But this was a different kind of reward for group cohesion, because this tune has two riffs and seven players take it in as many directions at once. The astonishing double-triplet Diamond Williams drops into his drum intro is of a piece with his eschewing a straight four throughout – he has the whole band surfing on a bag of marbles. Only Sugar Bonner’s cackling vocal interjections are clearly on the one. Billy Beck’s synth part could be Hindemith. And it jams. So, saying that someone died making this is just . . . redundant.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Friday, December 1, 2023

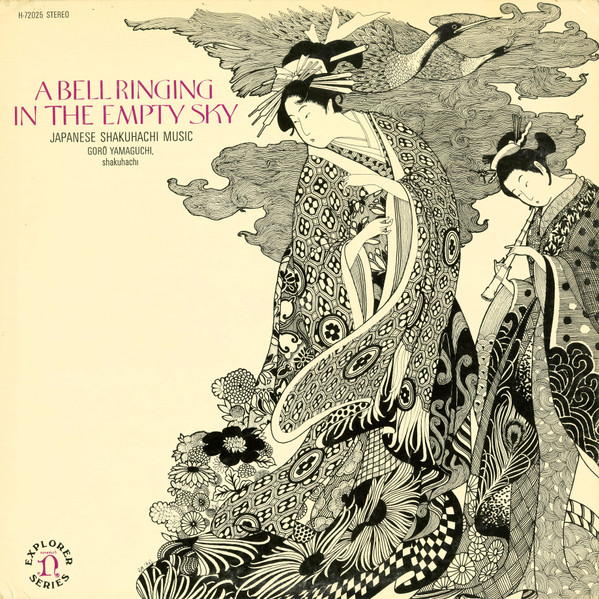

5. Sokaku-Reibo ツル の 巣ごもり(Depicting The Cranes In Their Nest)

Yamaguchi Gorō 山口 五郎: A Bell Ringing In The Empty Sky: Japanese Shakuhachi Music

(Nonesuch Explorer Series, 1969)

I have heard a fair number of solo shakuhachi records since I first heard this one, some years after it was recorded during Yamaguchi’s residency at Wesleyan in the late ‘60s, and immortalized for outworlders with an excerpt etched on to the gold-plated disc bolted to the Voyager probe. It is also my one reliable answer to the “Desert Island Discs” question, not only because it is my favorite recording of any kind of music, but also because it illuminates that just-for-fun question in the most serious possible way: instead of the futility of trying to retain some grip on your old life by taking some capsule summary of it on a piece of plastic with you, what kind of information structure would best suit indefinite solitude? Not melodies, but unbroken lines with no possibility of harmonic context, let alone any need for one, because more notes would crowd and jostle what is there and brimming over the rim. It is a slip of paper on a pool of water bent in just enough places to make a boat – maybe just one will do. Which not coincidentally is also my one reliable answer to another just-for-fun question: what is art?

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Thursday, November 30, 2023

4. Symphony №5 in D minor, Op. 47: First Movement (Moderato)

(Premiered Nov. 21, 1937, with Yevgeny Mravinsky conducting the Symphony Orchestra of the Leningrad State Philharmonic);

composed by Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (1906-1975)

If you know Shostakovich, you probably know this symphony. If you know this symphony, you probably know that Stalin’s positive response to it was the only thing keeping the composer out of the Gulag. He was their best beyond question, and even Stalin apparently thought so. Just that every now and then the apparatchiks made him pule like a whipped dog on cue because too many pointy-heads at liberty have a way of slowing History down, despite bringing the nonpareil socialist flavor. But he was Shostakovich and he puled like he did anything else. In the first movement, the trumpety pageant of inexorable history thunders past, but in the last minute, the strings go almost completely quiet while an unprepossessing secondary theme introduced earlier, is reintroduced as a smiling curse: a lonely solo theme played first by piccolo, then seconded by violin. A pule like disobedient history. Bulgakov had to keep the manuscript of The Master and Maragarita literally buried when he was not writing it, as if his words might run away and denounce their author. Shostakovich had no choice but to put an equivalent insult in plain sight. But he put it where no one dared touch it.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

3. Barangrill

Joni Mitchell: For The Roses (Asylum, 1972);

composed by Joni Mitchell

Asking when Joni Mitchell “peaked” is just stupid, because all that means is when did she peak for you. Talent that humongous just needs to connect, and for me – like many – she connected most on her first eight albums. After Hejira (which I actually find a little windy), she kept connecting, but mostly not. This anomalous tune comes right in the middle of the period when all she had to do – commercially and artistically both – was push, and people are still trying to figure out what hit them. Coming after Blue, her most “confessional” album, For The Roses splits its twelve songs evenly between her piano and guitar and its pronouns between “I” and “you,” except for this picaresque narrative for guitar and woodwinds about people who sound a little desperate, but are, for just seconds at a time, ecstatically happy – about earrings, tires, cocktails, and Nat King Cole. The spare instrumentation sounds almost orchestral wrapped around the cadence of her voice, which obviates any set meter. It is the saddest song about happiness I have ever heard. Her best next move was to find a drummer who could follow her, and we are lucky that it was John Guerin.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

Monday, November 27, 2023

2. Little Cow And Calf Is Gonna Die Blues

Skip James (Recorded Feb. 1931; released on Paramount 13085, b/w “How Long 'Buck'”); composed by Nehemiah Curtis James

Somewhat miraculously, all of the just eighteen sides Skip James cut for Paramount in 1931 have survived. On five of them, he played piano rather than the open D minor guitar that still makes the biggest impression on newcomers. Much of the latter impression comes from the way he sang so seductively over his relentlessly lilting guitar figures, in a sinuous falsetto both sorrowful and utterly pitiless, with lyrics to match. What is also unsettling about that voice is the way its seductive character simply vanishes on the piano sides. Arguably, James could not really play the piano – he banged out triads in several different tempos at once and almost distractedly crammed words into the cracks and breathless ha-aha-has. But this other weirder approach not only validates the guitar sides, it also suggests the breadth and depth of James’s overall concept. The effect is less Thelonious Monk than Cy Twombly – a deliberately primitivist approach elucidating a unique information system. The words, the notes, and the cursed feelings are all stones in his passway, piled into cairns leading the way to a hell planet. What happens when a first-order intelligence runs smack into the meanest adversity? Very occasionally, something like this.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day during Advent (approximately).

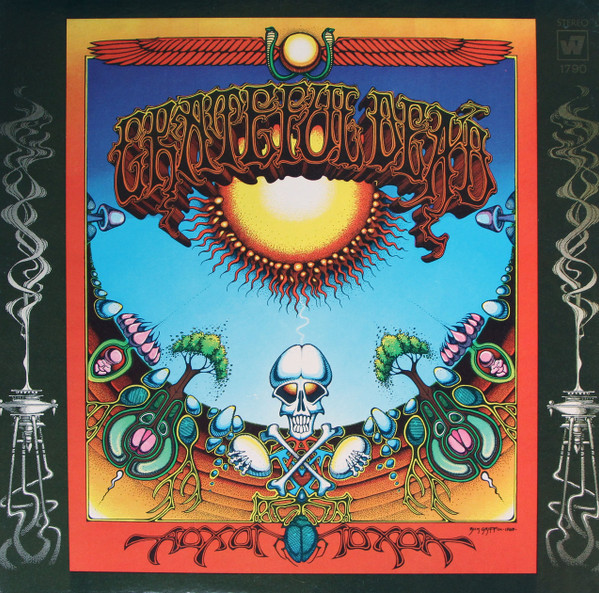

1. What’s Become of the Baby?

The Grateful Dead: Aoxomoxoa (Warner Bros., 1969);

composed by Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter

This may be the most alien track from the Dead’s most lysergic album, and I do not know anyone who loves it, let alone plays it often. I do play it, however – both the original and the 1971 remix, and no other track on Aoxomoxoa was so utterly – and mysteriously – transformed. For eight minutes and change, Jerry Garcia sings a Robert Hunter poem about Jesus (I think) through a ring modulator, improvising a melody from a fixed set of pitches. How does it compare to Stockhausen’s “Gesang der Jünglinge,” to pick an utterly non-random example? No idea. Same planet, if not jukebox. But how does it compare to the rest of Aoxomoxoa, not to mention everything else that happened after the Dead stopped going into debt to make albums that sounded like the supernovas in their heads? Well, same jukebox, if not planet. There is a delicacy to Hunter’s lyrics on this album – an air of questing gobsmacked generosity to fragile compatriots that carried over to the more accessible tunes on the subsequent albums that put them well into the black, while permanently confusing their mass audience about the cost of what they had put themselves through to get there.

Note: 25 secular essays about 25 songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (approximately) during Advent.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)