Sunday, December 21, 2025

139. Jesu, Meine Freude, BWV 227

composed by Johann Sebastian Bach

The definition of “motet” is exceedingly vague. Ostensibly, it is usually a short multi-part choral piece for a small group, usually upon religious themes, and often unaccompanied by any instrumentation. Bach’s six known motets take this last point to a fascinating extreme insofar as although his motets have instrumental parts, the vocal writing is so rich and so flush against the accompaniment – organ or small chamber group – that even with a small chorus you have to listen with a great deal of concentration to be certain that there are any instruments playing under it at all. Accordingly, they are the most hermetic of this avowed Lutheran’s works – maybe not as conceptually taut as Art of the Fugue, but immeasurably more beautiful. This is the longest motet of the six, which are my favorites of Bach’s catalogue of extant works which number well over 1000. The title translates to “Jesus, My Joy” and the text is divided between Chapter 8 of Paul’s epistle to the Romans and verse by one Johann Frank: “Defiance to the old dragon, defiance to the vengeance of death, defiance to fear as well! Rage, world, and attack; I stand here and sing in entirely secure peace!”

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

138. Spacelab

Kraftwerk: The Man·Machine (Kling Klang/EMI, 1978);

composed by Ralf Hütter & Karl Bartos

My favorite story about Kraftwerk is Tina Weymouth’s anecdote about meeting Ralf Hütter and trying to break the ice by complimenting Kraftwerk’s lyrics, only to have him snap, “What?! The lyrics are stupid!” This self-assessment is basically accurate, but Kraftwerk’s lyrics are a very peculiar kind of stupid – as is this group’s overall aesthetic of human beings looking and behaving as much like automatons as possible and playing what they conceptualize as music that only machines would enjoy let alone make. The irony is that once they abandoned what they had in common with other motorik German groups that favored repetition like Neu! (an early Kraftwerk offshoot) and turning their mechanized sound and imagery into a Constructivist cartoon, they started making very singular and strangely emotional pop music out of it. This track has no lyrics other than the title, repeated through a vocoder, interspersed with a melancholy Schubertian theme, against the same kind of synthesized bottom that activated Giorgio Moroder’s production of Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love,” but harder, more angular, and more unrelenting. The resulting effect is strangely soft and beautiful, just as contemporary extruded disco mixes began opening up emotional territory that songs themselves could not touch.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

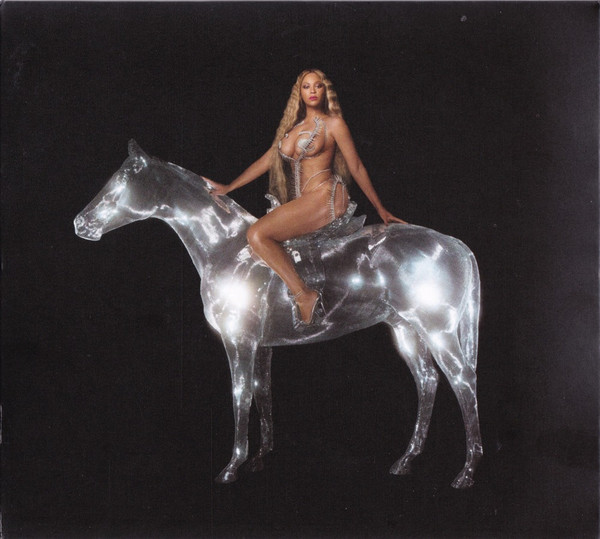

137. Plastic Off The Sofa

Beyoncé: Renaissance (Parkwood Entertainment/Columbia, 2022);

composed by Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter, Sydney Bennett, Sabrina Claudio, Nick Green, and Patrick Paige II

I was a late adopter of Beyoncé, basically because the first decade or so of her busterblocking post-Destiny’s Child career seemed so obvious. I liked “Crazy In Love” fine, loathed “Halo” much, and felt mostly uninvolved with all of it. The kind of Big Pop with a half dozen composer credits per track has no intrinsic need for me to like it, shall we say, so its pleasures tend to hit me in an unscheduled way. Consequently, half the planet already knew that Beyoncé in 2014 was a massive reinvention years before I listened hard and figured it was not only more a reinvention of the whole concept of reinvention, but also that reinvention was a feat that each of the three epochal albums that have followed since have managed in turn. Two of this track’s five co-composers were key members of The Internet, an under-sung offshoot of the long-gone Odd Future collective. Together, these weirdos craft a side-winding evocation of sex that unapologetically stains the upholstery: “I know you can't help but to be yourself 'round me . . . And I know nobody's perfect, so I'll let you be.” I could be wrong, but that sounds like Jay-Z to me.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

136. Ich Habe Gelernt (I Have Learned)

Lotte Lenya & Heinz Sauerbaum with Wilhelm Brückner-Rüggeberg, cond.: Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Columbia, 1956);

composed by Kurt Weill & Bertolt Brecht

This 1930 opera – a fable about an imagined (and geographically confused) American city where the only punishable offense is not being able to pay your bills – was the last project Weill and Brecht did together before Weill bridled at Brecht’s much-harder-left politics and went his own way – and very shortly before both of them had to run for it upon the advent of the Austrian corporal. Not nearly as well-known as Threepenny Opera, it shows the strain of having been expanded from a shorter piece (the Mahagonny-Songspiel). To my ears, the expansion resulted in a comparatively draggy second half, but the first half is a treasure house. The best-known number is the “Alabama-Song” (covered by the Doors), but the prize is this brief anomalous duet between a prostitute and the hapless protagonist Jimmy. After haggling over the fee, she says, “I have learned, whenever I meet a man, to ask him what he is used to. Therefore tell me how you would like me to be.” Accompanied by a solo saxophone playing one of the most melancholy melodies ever written, he tells her. When asked about her wishes, she replies, “It is perhaps too soon to talk of them.”

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Saturday, December 20, 2025

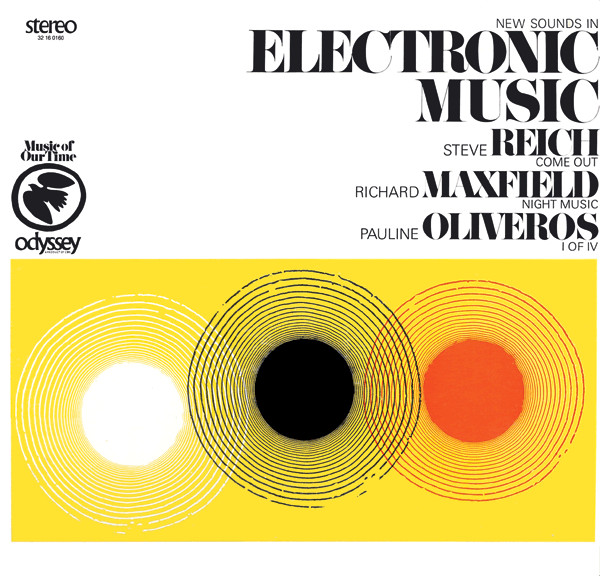

135. Come Out

Steve Reich / Richard Maxfield / Pauline Oliveros: New Sounds In Electronic Music (Columbia/Odyssey, 1967);

composed by Steve Reich

Composers that get called “minimalist” really hate that term – I once saw Philip Glass shut a questioner down just for using the word – because it is not relevant to their actual objective, which is to use whatever means are most appropriate to bringing out qualities that other musical forms and strategies do not. A lot of it may sound merely repetitious to some, but if you bring full attention to it, you acquire a kind of third (and fourth) ear that zeroes in on the interstitial information that tumbles sideways out of the music. This early piece by Steve Reich is kind of an acid test for that idea, in multiple senses of the term. A fragment from a taped interview with a gentle-voiced victim of a police beating relating how he had obtained medical treatment by making one of his bruises bleed again – to “come out to show them” – which phrase is repeated on multiple tape loops in tandem which gradually – and then rapidly – go out of phase with each other, until the overlapping vocals sound like engines or hundreds of beating wings. It also turns the phrase into a political wake up you can feel in your bones.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Friday, December 19, 2025

134. Moisture

The Residents: Commercial Album (Ralph, 1980);

composed by ? ? ? ?

The Residents acquired their avant-ish cachet as much for their Pynchonesque refusal to identify their individual members as for their music which usefully served to deflect attention from both. The music was still the point, but the genial hostility of the presentation – their “management” gave interviews speaking about the group in the third person in voices nonetheless recognizable from the records – gave the musical usages a little more breathing room than they might otherwise have. Others may disagree about their later theatrical incarnations, but I think this album was their apotheosis, conceptually: an album of forty tracks each lasting exactly one minute, yet each making an impression. None have much of a beat; most of the instrumentation is rudimentary synths with voices mewing microtonal melodies almost-tonal-but-not on top. The effect is not so much distortion as decay: as if this technologically oriented music had been fashioned from biomatter that was audibly decomposing - as if DEVO were Weird Al Yankovic. On this emblematic track, two verses are separated by a jazzish Fred Frith guitar solo. In the first, a “stranger” is observed perspiring a lot. In the second, they find a snail in her purse after she dies. Time passes.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Thursday, December 18, 2025

133. God, What Am I Doing Here?

The Holy Modal Rounders: Last Round (Adelphi, 1978);

composed by Barbara Ann Goldblatt

I do not mean to be insulting, but I suspect that this song may be perfect, if you can imagine the Absolute having multiple flavors and toppings. Its author, who answered to Antonia, occasionally adding Duren or Stampfel to it, was one of the primary songwriters for a group she made possible by introducing its two original members to each other. Whether she was a performing member of the group herself would have to be confirmed by eyewitnesses, because it is not entirely clear from the extant but strangely evanescent recordings. She wrote the song that came nearest to being a hit – “Bird Song” – when it was included on the Easy Rider soundtrack. She also wrote “Fucking Sailors In Chinatown,” which did not appear on record until this century. And she also-also wrote the single greatest songful meditation on human existence in the language (since Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps has no words and would be in French anyway): “The cold wind from space / Is blowing in my face. / God, what am I doing here?” The question is both a cosmic conundrum and a sputter of exasperation, like Bette Davis saying, “What a dump!” in Beyond the Forest.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Wednesday, December 17, 2025

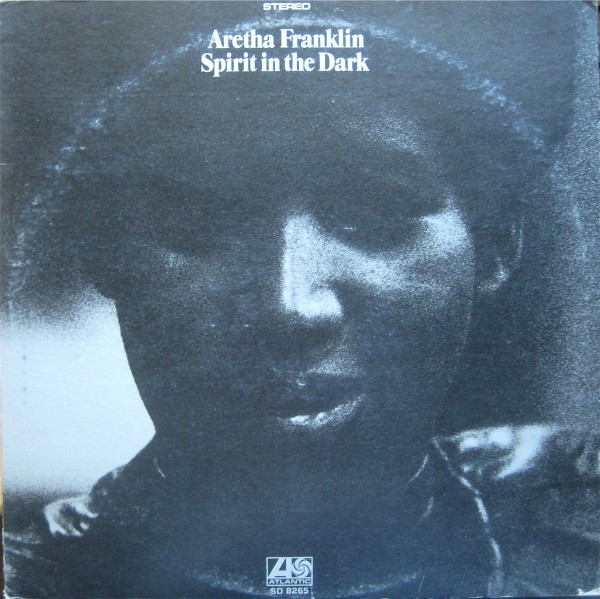

132. You And Me

Aretha Franklin: Spirit In The Dark (Atlantic, 1970);

composed by Aretha Franklin

One great thing about Aretha Franklin as a phenomenon is that you cannot praise her fulsomely without leaving out something key. An absolutely nonpareil singer, most obviously, but a terrific pianist as well – she plays on all of the greatest Atlantic sessions, cuing up everything that the best musicians in the country at the time did on her records. But then you miss what a great songwriter she also was. She had bigger self-written tunes than this track and bigger (if not necessarily better) albums than this great one, but so much about both was just so right in so many singular ways. The backup musicians on half this album were the Muscle Shoals crew, but the other half were the Dixie Flyers, the house band at Criteria Studios in Miami, who had not backed her up on record before and play on this track. Everything is keyed to her piano, which has an intimacy very much like having a lover wake you up just by breathing, aptly setting a lyric conveying a similar affect: “We've got our strength and our love for all mankind / But most of all, we've got peace of mind.” Did she, really? Maybe. Here, indubitably.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Tuesday, December 16, 2025

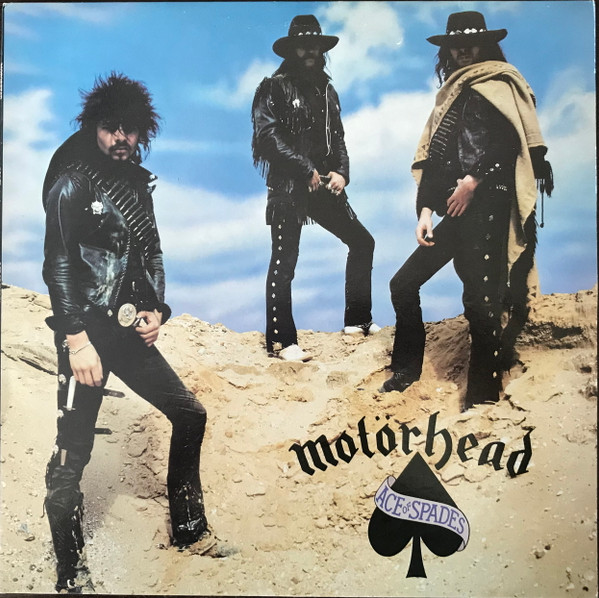

131. Ace of Spades

Motörhead: Ace of Spades (Bronze, 1980);

composed by Ian Fraser Kilmister, Edward Allan Clarke, and Philip John Taylor

From the time that super high-definition guitar noise became feasible and readily monetizable in the late 1960s, and insofar as that sound was tethered to pop music forms – i.e. songs with sung words – one of the most formidable formal issues has been what sort of words are a natural fit with that unnatural, technologically fabricated sound. Do you proceed as if the unnaturalness was not there by puffing up the grandeur of the meat robots doing the playing, or do you address the technological displacement directly even if you look a little abject? One of my pet theories is that the former is a capsule definition of heavy metal, while the latter does likewise for punk. And one of the many charms of Motörhead was how Lemmy Kilmister’s long-running concoction flipped two fingers at the distinction and confused everybody too thick to get his point. Motörhead were plenty loud and plenty fast, but Lemmy projected a very singular personality as a bellowing frontman – hectic to know, but funny as hell in an oddly introspective kind of way, as in this diffident praise of poker: “The pleasure is to play, Makes no difference what you say, I don't share your greed.”

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Monday, December 15, 2025

130. Chinatown (Main Title)

Chinatown - Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (ABC, 1974);

composed by Jerry Goldsmith

I have never gotten with the phrase “Love Theme from” although that is the official designation of the music that plays under (or with) the opening credits of this great rewired noir written by Robert Towne and directed into perdition by Roman Polanski. But here the designation is more than fair – love is fucked up. And sometimes a film’s makers reject one score and hire you to compose an entirely different one in ten days, and somehow under deadline you come up with a theme that acts like a full recursion of the film’s emotional mayhem – the deepest longing handcuffed to an unconsolable abyssal plunge. The music starts in one bright key with a strum of muted harp strings and wispy upward phrases, and seconds later drops precipitously into a theme on solo trumpet with piano counterpoint played in a completely different key like a trap door opening under you. I do not know of any other movie theme that touches it – maybe one or another of Nino Rota’s – and it is so wedded to its context that covering it is out of the question – unless you are John Zorn and precede your version with three minutes of thrash punk.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Sunday, December 14, 2025

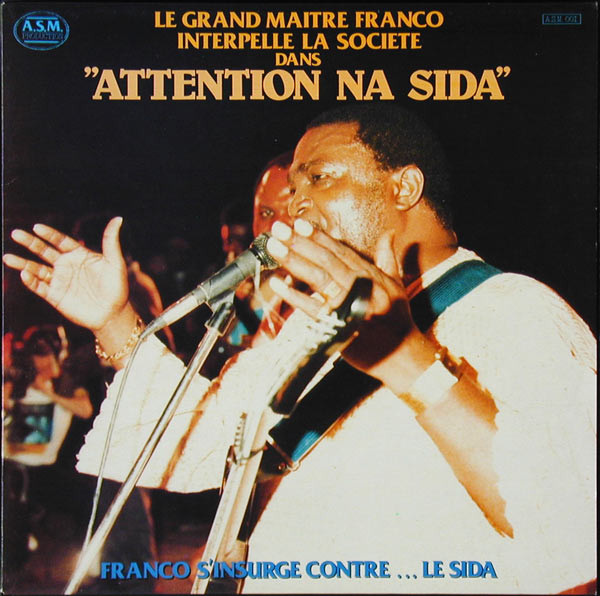

129. Attention Na SIDA

Le Grand Maître Franco & Orchestre Tout Puissant O.K. Jazz: Attention Na SIDA (African Sun Music, 1987);

composed by François Luambo Makiadi Lokanga La Djo Péné

From the perspective of the western audience for African pop music (Hi, there!), Franco is crudely perceived as being to Zaïre (he did not live to see the name of his country return to “Congo”) what Fela Kuti was to Nigeria. They were both giants by any standard, of course. Franco, a great singer, guitarist, and bandleader, was a prime co-inventor of a transmogrified rumba called soukous, in which multiple interlocking guitar parts spin out over a Cuban-tinged pulse that tended to start a number serenely and then, at an agreed nexus, shift into an intense irresistibly danceable boil. The other unfortunate commonality with Fela is that AIDS took them both away, although Fela – contrarian that he was – denied it all the way to his death in 1997. In contrast, Franco released this public service message about the menace – in French rather than the Lingala he usually sang in – even before his own diagnosis. Uncharacteristically, there is no quieter opening section to this tune – it starts at boil and continues at full intensity for sixteen minutes (on record – live it could have gone on far longer). Apart from the words, it sounds mostly like the greatest party ever. Probably was.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Saturday, December 13, 2025

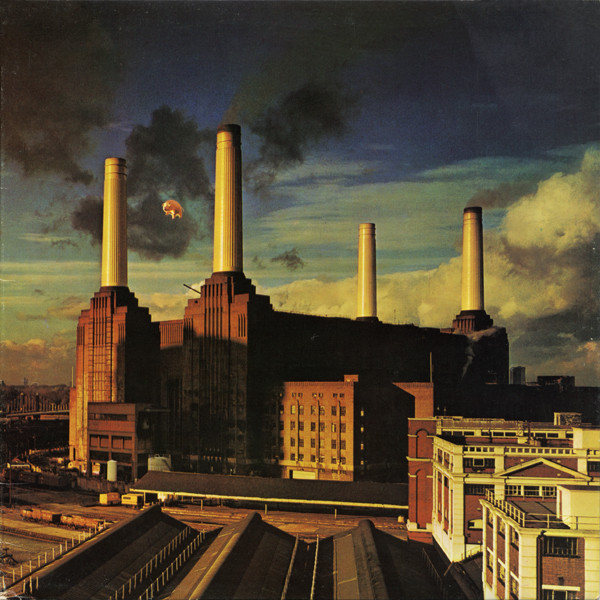

128. Dogs

Pink Floyd: Animals (Columbia, 1977);

composed by Roger Waters & David Gilmour

The greatest compliment I can pay to the vaunted “concepts” at work in Pink Floyd’s skadillion selling ‘70s albums is that you can ignore them altogether and at the same time they made the music what it was just by lending a kind of internal armature for what was basically an amorphous but still remarkably distinctive sound concept. The songwriting was neither here nor there after Syd Barrett checked out – and his tunes were pretty amorphous too, but they were concisely so. So although Roger Waters’s imprecations against rat-racing capitalist running dogs are no more acute than those in “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” contextualizing them resulted in this hilariously spooky haunted house music with cool guitar parts that holds up remarkably well for seventeen minutes solid. This track was fashioned from what was basically a leftover from the sessions for Wish You Were Here, which works better as a discrete unit than Animals does, in part because after months of flailing at a follow up to Dark Side of the Moon, they stumbled into a working method that worked even better. They got one more good album out of it, tailored to a collective aural identity, before Waters’s concepting swamped it.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Friday, December 12, 2025

127. Triad

The Byrds: The Notorious Byrd Brothers - unreleased (Columbia, 1968);

composed by David Crosby

For better or worse, there was probably nobody who believed in hippiedom more than David Crosby. He also exemplified how it differed from other forms of alternative culture before and since - some of the more visionary genuinely thought they were closer to some kind of future normal than the straight world in its fatal contradictions could possibly remain. Except that fatal contradictions are, in Brecht’s terminology, how mankind stays alive, if you can call it that. This track was recorded for the Byrds’ last great album just before they kicked him out for being an arrogant asshole (ultimately, he agreed with that assessment) and it would have added an even spacier dynamic to the cross-faded spacy masterpiece that Roger McGuinn fashioned out of what was left when they dropped this song (and Crosby gave it to Jefferson Airplane). Ostensibly, the song is about a threesome. More to the point, the song is also about what it might be like if no one was afraid of what they wanted most – not excluding “water brothers,” a now-quaintly archaic term for gay men, and not at all a common or publicly expressed sympathy, even then. An arrogant asshole who truly meant well.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Thursday, December 11, 2025

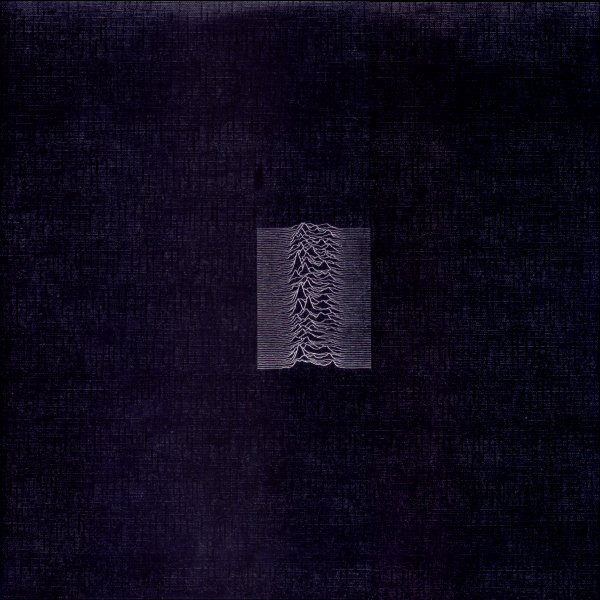

126. Shadowplay

Joy Division: Unknown Pleasures (Factory, 1979);

composed by Ian Curtis, Peter Hook, Stephen Morris, and Bernard Sumner

I rarely speculate on what might have happened if any artist who dies or otherwise absents themselves had not done so – and Ian Curtis might as well be the face on that particular milk carton. Insofar as his collaborators had more than enough juice to reconfigure themselves as New Order, a very different band with a comparable albeit rather more cheerful legacy, Curtis was lucky. But they all were. Each of their two albums signifies in a different and equally plangent way. Depression was Curtis’s great (or primary) subject, but on Closer (too appropriate a title), it defined the parameters and the often almost static spaciness of the music, while Curtis’s disinclination to sing on key ever again squared the circle. On the debut Unknown Pleasures, however, music and topic collided at steeper angles. This track might be the most rocked-out thing they ever recorded, but in a way unique to them and their weird-ass producer Martin Hannett: tension, dynamic shifts, and dead space delineated by bass and skeletal drums, setting up infusions of almost orchestral guitar noise alternating with a creepy single-note figure answering Curtis’s grim ruminations. Can depression actually sound cheerful? No, but it sure can be precise.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Wednesday, December 10, 2025

125. Southern Can Is Mine

Blind Sammie (Columbia 14632-D, 1931 – b/w “Broke Down Engine Blues”);

composed by William Samuel McTier (a/k/a Blind Willie McTell)

I have no ready rationale for writing about a tune so egregiously misogynistic - even by the standards of a century ago - so it becomes more a matter of facing it squarely. The fact that it was written and recorded (twice – for two different labels) by one of the genius performers of that time does not make it less “problematic” (as we say now), because the song also exemplifies McTell’s uniqueness and power: the incredible rhythmic drive and volume he got on a 12-string guitar and the slippery rhythmic counterpoint of his voice. So why not just write about “Statesboro Blues”? Because it is tantalizing to wonder how McTell’s light tenor could make lyrics about threatening to beat up or pimp out his girlfriend if she holds out on the sex, which also sounds distinctly unpleasant (and for those just joining us, “southern can” = ass), sound almost . . . cute. Not that actual cuteness is in play, but even at his darkest McTell always sounded fun - like the thought of forbidden pleasures mattered most. In contrast, Skip James’ falsetto would have made these lyrics pitiless and bloodcurdling – he would have meant them and sounded like it.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Tuesday, December 9, 2025

124. Le Torture

Ennio Morricone & Gillo Pontecorvo: La Battaglia di Algeri (RCA Italiana, 1966);

composed by Ennio Morricone

What do you do with the parts that wrench the narrative out of shape, but refuse to be left out? Pontecorvo’s docudrama about France’s protracted exit from a colony many of them had considered a départment de la République has two essentials. One – comprising 99% of the film’s length – is the military victory of the Algerian insurgency, for which operations in the capital are emblematic of the wider war. The other essential is the fact that the French were hideously torturing Algerian prisoners which may have broken the French as certainly as the FLN did. Torture was so typical of colonial administrations that there might not have been reason to raise the issue had the Nazis not then-recently had the temerity to visit colonial methods upon other Europeans, which was only part of how that cataclysm made colonialism too costly. (Alternatively, the Argentine military reportedly used this film to prepare a counter-insurgency against its own citizens.) Morricone’s great soundtrack comprises a delirious martial frenzy for most of the film, until a montage at the end with no dialogue or other source audio – just images of bound prisoners being blowtorched and electrocuted, accompanied by a perfectly forlorn and bizarre organ chorale.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Monday, December 8, 2025

123. Rubber Biscuit

The Chips (Josie 803, 1956 – b/w “Oh, My Darlin'”);

composed by Charles Johnson, Nathaniel Epps, Paul Fulton, Sammy Strain, and Shedrick Lincoln

This song is best remembered today as Dan Aykroyd’s feature with the Blues Brothers, but if Aykroyd’s relative subtlety set off Belushi, then the original version of this makes Aykroyd’s seem like a sack of doorknobs. The song is a novelty number featuring a lead scatting nonsense syllables over an uptempo harmony group who all come to a periodic halt for the same lead to deliver a series of giggling gnomic jokes about being broke and hungry. What makes it absolutely brilliant is what the Bros left out – the feather-light timing. One rap goes: “The other day I ate a ricochet biscuit. Well, it’s the kind of a biscuit that's supposed to bounce off the wall back in your mouth. If it don't bounce back – [sobs] – you go hungry!” On the Chips record, the sobs between those phrases are a weird airburst lasting a single beat. Then the ensemble comes back a whole beat sooner than you expect them to – like someone pulling your chair out from under you. Some may also remember it playing in Mean Streets when Harvey Keitel’s character is getting quickly wasted in a bar and Scorsese’s camera follows him all the way to the floor.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Sunday, December 7, 2025

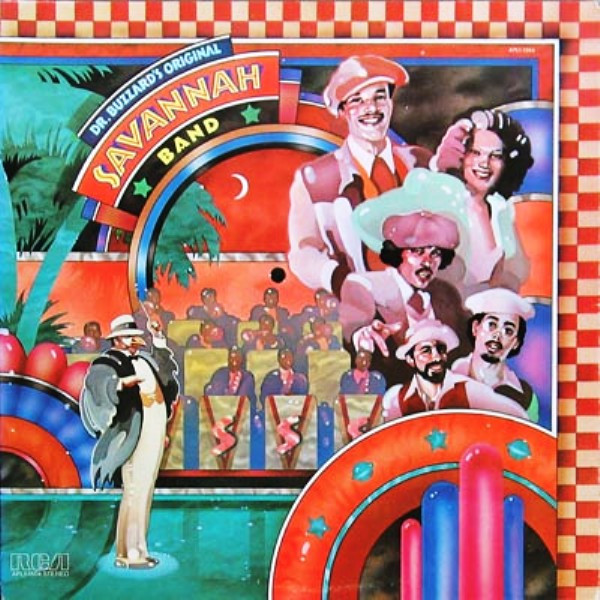

122. Cherchez La Femme

Dr. Buzzard’s Original “Savannah” Band (RCA Victor, 1976);

composed by Stony Browder Jr. & Thomas August Darnell Browder

There was no better or weirder nostalgia act than this group, because they really meant the nostalgia part – they made it intellectually challenging rather than the revolting pander it became in the mid ‘70s. On this track, their tune is just under three minutes, sandwiched between two-minute-long covers (more like lengthy quotes, but the kind you have to pay royalties for) of “Whispering,” a hit from the ‘20s, and “Se si bon,” from the late ‘40s. The latter decade is how they styled themselves rhythmically as well as sartorially, but they did nothing to conceal the electric instruments and synths – everything just fit together. And it went to number one on the Dance chart for a reason: it may not have sounded up to date rhythmically, but it felt that way, and it made the song hyperconductive – which defines Disco far more succinctly than a uniform 120 beats per minute. Neither was there anything feel-good about the lyrics – sung by the utterly brilliant Cory Daye – which are about various characters (including their manager) coping with general misery by “cherchez la femme.” As in its original sense as a French proverb, this has remarkably little to do with getting laid.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Saturday, December 6, 2025

121. Ихесъ (Yikhes)

Belf’s Rumanian Orchestra (Syrena Grand 11079, 1912 – b/w Сихмасъ-Тойре)

I know very little about this group or this record. No one does, and it is not just that we are a century and change apart – this record could have been top of the pops on Krypton. Yet this crackly 78 is so pop in its way, if you get it all the way in your head. They were not actually “Rumanian” – that was a term of art, as was “Bulgar” or “Odessa,” both as those cultures influenced the music over time and as euphemisms for “Jewish” – as was “Klezmer,” a centuries old term loosely translated as “musical instruments.” Yiddish speakers might get more out of the song’s title than Google Translate, which renders it in English (ha!) as “Yikes!” There were any number of very similar Yiddish-speaking dance orchestras around the western part of the pre-WWI Russian empire at the same time, but this one was fortunate enough to be recorded by an enterprising record company in Warsaw, and the records sold well enough for copies to still exist. Although emigres like Abe Schwartz and Naftule Brandwein got Klezmer going over here within a decade, this music is like what jazz might be if someone had recorded Buddy Bolden.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Friday, December 5, 2025

120. Take My Hand, Precious Lord

composed by Thomas A. Dorsey

This may not be the premier gospel song of the previous century, but I doubt that there is any other that connects with so much of that century. Martin Luther King Jr.’s last written words were a request that this be played “real pretty” at a (then-)upcoming service. Mahalia Jackson sang it at his funeral. Its author composed it in part as a way of dealing with the deaths of his wife and son in 1932. Dorsey had only just recently returned to religious music after being half of Tampa Red and Georgia Tom, a great blues act of the 1920s, and key accompanist for Ma Rainey. Nitpickers point out the melody’s many antecedents, but more intriguing is that it does not really have a melody. The recordings of the song I know are all different, except for its trademark cadence – the rising uplift of its first three phrases: “Precious Lord, take my hand, lead me on.” – a plea to the great unknown for divine influence. On its first commercial recording in 1937, the Heavenly Gospel Singers sang it as a shape note hymn with no melody at all. Mahalia barely departed from the tonic. Elvis Presley did nothing but.

Note: Secular (mostly) essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Wednesday, December 3, 2025

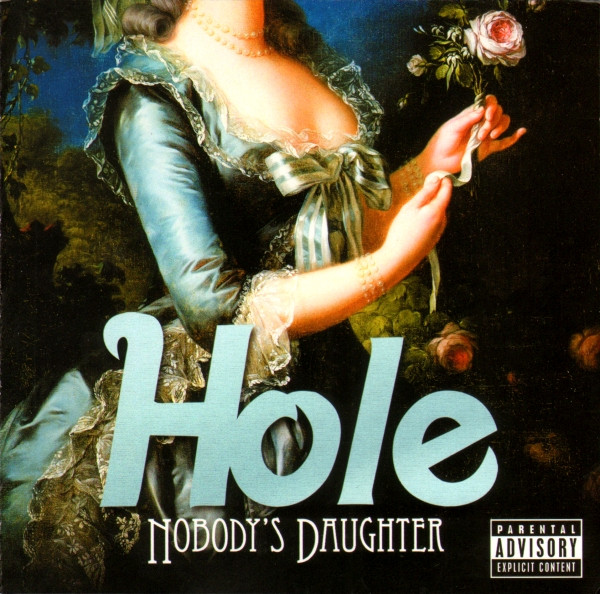

119. Skinny Little Bitch

Hole: Nobody’s Daughter (Mercury/Cherry Forever, 2010);

composed by Courtney Love & Micko Larkin

Insofar as Frances Bean Cobain survived into adulthood many years ago, any reasons I might have for disliking Courtney Love from this distance are pretty much irrelevant. I am sure she is incredibly hectic to know, but yards ahead of everybody else in the room most of the time, and that correlation is the proverbial rub. She recalls Eve Babitz, without the late-breaking reactionary turn (which could still happen – she was tight with both Kanye and Russell Brand before they went over), and even if we never get any books, we do have all of those lovely nasty records of hers. This track from a later edition of Hole is her flavor of archetypal. The skinny little bitch dissolving in bad dope and dopamine could be Courtney herself, or some alternate version that burned up like magnesium long ago. Genuine cautionary tales risk seduction to render up their usable data, so she lays that ugly-tuneful rasp over ten-cylinder guitar noise and runs you over. Anyone who still thinks she leeched the life out of Kurt Cobain is never going to get it. All evidence points to her leeching it into him, and really - maybe that was what killed him.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

118. Love Is Strange

Mickey & Sylvia (Groove 4G-0175, 1956 – b/w “I’m Going Home”);

composed by Ethel Smith

Composed by Bo Diddley (but credited to his wife at the time), his original recording of it - not released until decades later on his Chess box set – shows its subsequent recasting by these two pros as the miracle of art and commerce that it was and remains. For one thing, Bo’s version really sounds like the title – love is strange, mysterious, oppressively hermetic in its disinclination to give forth anything like clarity, and his rueful performance follows suit. In contrast, Mickey Baker and Sylvia Robinson make it sound more like a Bo Diddley record than Bo’s version does – a struck gong and a call to whatever the secular equivalent of prayer might be. Mickey’s adamantine guitar figures over the tremelo rhythm are even more flagrant come-ons (and come-here’s) than the cooing vocal duet, notwithstanding the colloquy that caps the duet at the end: “Sylvia?” “Yes, Mickey?” “How do you call your lover boy?” Mickey continued to play killer guitar for all kinds of acts over here, until he moved to France in 1962 and played killer guitar there. Sylvia went solo, palled around with gangsters, and brought us the Sugar Hill Gang and Grandmaster Flash. Fucked them over, too.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Tuesday, December 2, 2025

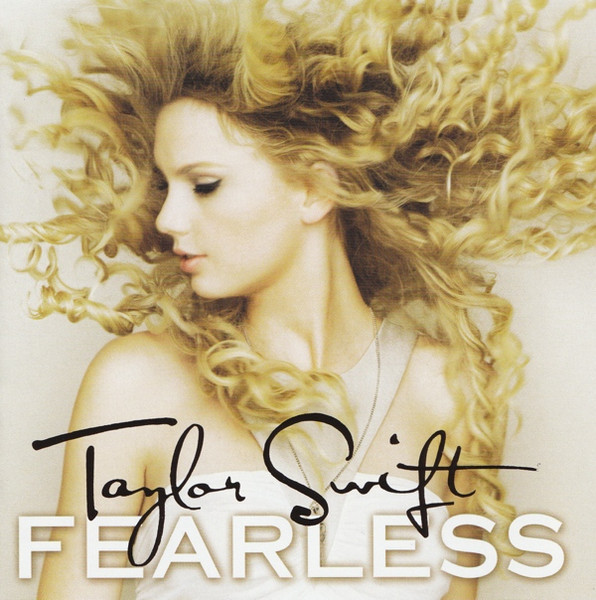

117. The Best Day

Taylor Swift: Fearless (Big Machine, 2008);

composed by Taylor Swift

Even if I disliked Taylor Swift, I do not argue with forces of nature, and to paraphrase what Mr. Spock once said about a killer robot, “I do not believe there is much beyond Taylor Swift's capabilities,” which is as much threat as admiration. Taylor Swift is a giant in every sense that counts. Not only does she do impossible things, she does things that are impossible because they really ought to be impossible – like writing this utterly sincere and dulcet love song to her mom. The first version came out when she was eighteen. She remade it along with the rest of her then-Scooter-Braun-controlled catalogue when she was thirty-one. It sounds the same as the first – slightly more alto, but not a hair less genuine. The video has a different but equally idyllic selection of childhood videos as the original video had. Many of us develop a sense of irony because we resent the way forces of commerce and public authority generalize and exploit emotions. The irony of Taylor Swift is that she has become the hugest pop star of the moment by doing the opposite. Tunefully, too. My sole complaint is that her albums run a little long.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Sunday, November 30, 2025

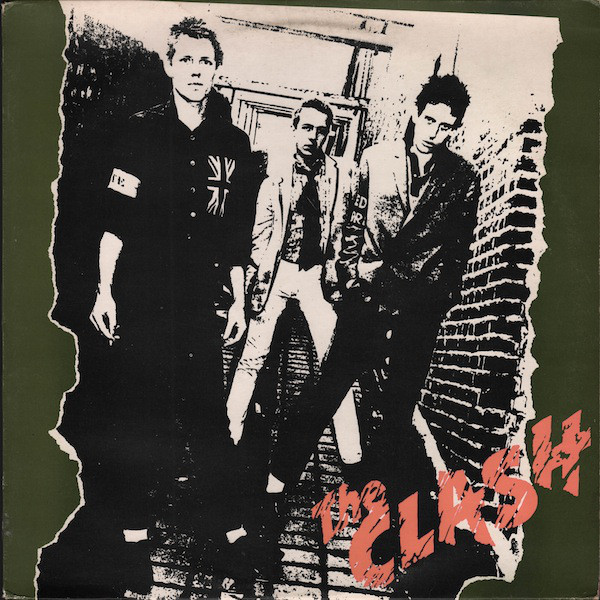

116. Deny

The Clash (CBS, 1977);

composed by Michael Jones & John Mellor

The Clash’s amphetiminic UK debut is the only one of theirs I still listen to with rapt pleasure beginning to end. They gizmoed it up for the U.S. version two years later, and if I was as intent on cracking that market as they had to have been, I might have done likewise, because the original 14-song disc would not have done it – it is just too perfect an evocation of too specific a state of mind. Unlike the cramped urban miniatures on Wire’s debut the same year, there is a weird jolliness to the Clash’s version of mid-‘70s London paranoia, albeit not one iota less bitter. Unlike the other three tracks the U.S. version omitted, this tune is actually catchy, but sitting smack between “What’s My Name” and “London’s Burning,” it lays the whole weird game out: “You’re such a liar / You’re selling your no-no all the time.” The latter is a slang term for salespeople who lose their knack and start talking themselves into refusals over and over. Funnier as it is, this is what “Janie Jones” is about, too. Once the Clash figured out what they were selling, they could not make any more like those.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

115. Redemption Song

Bob Marley & The Wailers: Uprising (Tuff Gong/Island, 1980);

composed by Bob Marley

Without knowing how close to death Bob Marley was when he recorded this, I am not sure how you would be able to tell from listening to it, but a couple of things catch my attention every time I do. There is the sinuous inescapable melody that could have easily been arranged for the whole band if Marley had been so inclined, with potentially cataclysmic results. Most obviously, there is the solo acoustic guitar accompanying a vocal that shows weariness only in the message conveyed, which is that time is beyond everyone. In these verses, neither pirates selling captives into slavery nor atomic power itself can do anything more to stop freedom – as consciousness no less than political actuality - than to slow it down just enough to raise doubts in those who do not understand how difficult an idea forever is. This man had none. He was a popular artist from the first, but he was also one of the very few who actually derived an almost mystical (his word, of course) connection with the mass audience – even the ones who tried to kill him. These were not his final words, but what a relief he got them out.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day through Advant and at least semi-regularly until Donald goes away.

Sunday, August 24, 2025

114. Naked Pictures (Of Your Mother)

Electric Six: Fire (XL Recordings, 2003);

composed by Tyler Spencer

There may be another recording act that got dropped by their label after their debut started selling too well, but this is the only one I know about and, in retrospect, it sort of figures. Masterminded by Detroit weirdo Tyler Spencer, Electric Six specialized (and still does today) in perhaps the only genuinely funny non-parody rock, insofar as it actually rocks in an appealingly disco-metal sort of way. And whereas Dylan or Lou Reed would stick embarrassingly mundane phrases in their songs just for texture, this particular number successively rhymes “dropped a bomb on Japan,” “hostage in Iran,” “ugly Ameri-can,” and “government man,” as though that last was a major money gig the singer had gladly sold his soul for, just so he could go to Taco Bell in a limo and set it on fire. The naked pictures in the title (and the chorus) do not appear to connect to anything else in the song. And Spencer cues the guitar solo by bellowing, “Solo!” Not everything on the album peaks so high in ridiculousness, and XL probably knew that Spencer would never quite get there again. But they have their audience, and they will take it to their graves.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (or at least regularly) until Donald goes away.

113. Gli impermeabili

Paolo Conte (CGD, 1984);

composed by Paolo Conte

Occasionally, it occurs to me how scary Leonard Cohen would have been if he had gone to law school, because such thoughts usually occur only because I happen to be listening to this ex-avvocato: a Piedmontese composer, pianist, and singer (sort of) who does the chansonnier-roué bit with a resonating sarcasm that inheres just a shade more musically than it does lyrically, which latter it unquestionably does, very much, also. This tune is proof of concept. The title, loosely translated, is “Raincoats.” A dulcet instrumental refrain intoned by massed cellos and single line guitar over a brisk four. On a rainy morning, Conte broods on romantic nights gone by and excuses himself to go get coffee. Key line: “But how well it rains on raincoats / And not on the soul.” Sound dopey? Conte evidently thinks so, too. He separates the lines with the deadest-possible-deadpan scat of “dah, dah-dah, dah-dah” like a dumb imitation of raindrops. Then on the last refrain he joins in on kazoo. It sounds even prettier. And the more ridiculous the juxtapositions, the more genuine the despair seems. People I play this for often tell me I must be joking to extol something so sweet. Probably.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (or at least regularly) until Donald goes away.

Friday, August 22, 2025

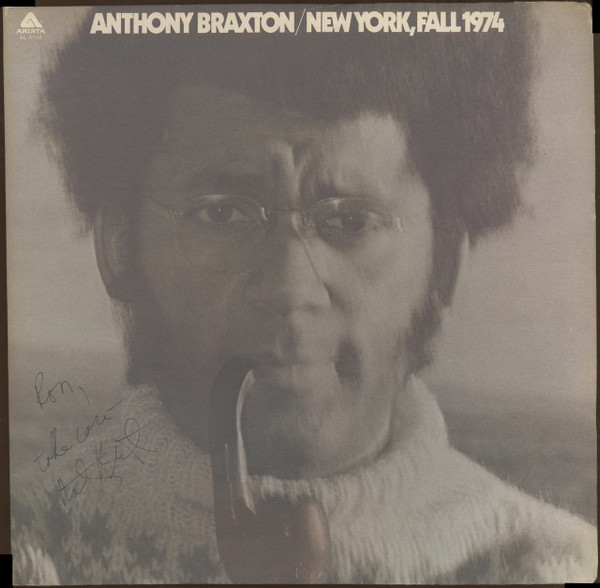

112. Composition 23B

Anthony Braxton: New York, Fall 1974 (Arista, 1974);

composed by Anthony Braxton

Anthony Braxton's discography is intentionally vast, which some skeptics view as of a piece with the obscurantist diagrams he uses for titles (see above), but non-skeptics (like me) take it all as the price of the oddball ticket, and unlike Sun Ra, the more of his oeuvre you get to, the more it coheres. This was not the first time an AACM luminary hooked up with a major label, but his Arista deal would be unusual at any time. Somehow Clive Davis authorized the release (however briefly) of nine incredibly varied and challenging albums, ostensibly underwritten by Barry Manilow's grosses. It could never last, of course - these deals never do - and Braxton made as much as he could out of it, while saving his 3-LP four orchestra piece for next-to-last. This opening track on the first of them might have been his signature number, if he went in for that sort of thing: a no-piano quartet playing a boppish head at light speed, with stop-time variations that sound just as load-bearing as the ostensible themes, which is like Charlie Parker rising from the dead, telling you to pull his finger, and having “Cherokee” in Z-flat major come out.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing not daily - but at least regularly - until Donald goes away.

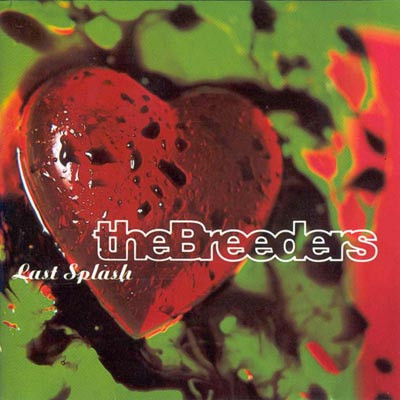

111. Cannonball

The Breeders: Last Splash (4AD, 1993);

composed by Kim Deal

By the early 1990s, “Indie” and “Alt” meant bupkes to me. A real war was when Journey or Eagles had been the enemy, but that was already way back then, back then. Rather, this was a time when thoughtful young people had gotten their heads around digital recording in a way the ‘70s holdovers never could, which unleashed a whole lot of possibilities for distorting aural scale. But whereas Soundgarden (for example) used the added definition to rev the guitar overtone saturation way up (a worthy goal), Kim Deal emerged from the disintegrating Pixies with her own counterintuitive synthesis. Instead of Jimmy Page’s analog trick of making Led Zeppelin’s human-scaled signifiers (voice and drums) as galactic as the electric ones, she did the reverse. You perceived the loud punky guitar bursts as just another logical part of a conversational grammar, abutting the unaccompanied light drum taps, acoustic chugs, and Kim and Kelley Deal’s just barely audible murmurs about splashes, bongs, and whateveryouwant. I was amused when journalists started asking Kim why the Pixies had never done any of her songs, after the Breeders outsold them. Because you need your own band to come up with something this perfect is why.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (or at least regularly) until Donald goes away.

Monday, August 18, 2025

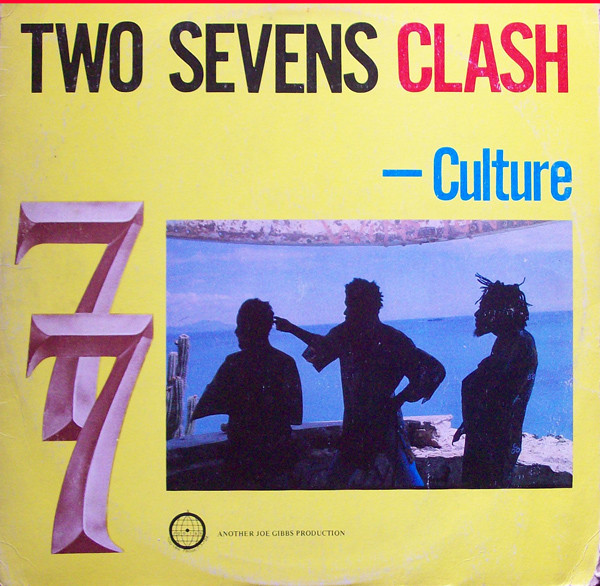

110. Two Sevens Clash

Culture: Two Sevens Clash (Joe Gibbs Record Globe, 1977);

composed by Albert Walker, Errol Thompson, Joseph Hill, Roy Dayes, and Vincent Gordon

One of my proudest possessions is a scratchy Jamaican 45 of “Beat Down Babylon,” by Junior Byles, that features the sound of a repeatedly cracking bullwhip with no apparent attempt made to sync it to the music – undoubtedly Lee Scratch Perry’s point: why should there be? Scratch’s colleague Joe Gibbs (also an occasional fill-in Wailer) intended a similarly aggressive aesthetic configuration in his production of this ultra-Roots vocal group’s debut, the title track of which details a long bus ride during which Joseph Hill espies a cottonwood tree destroyed by lightning (next to a police station, of course) and recalls a Marcus Garvey foretold cataclysm said to break over Babylon on 7/7/77. Supposedly, Kingston came to a near halt that day. “Wat a liiv an bambaie / When the two sevens clash,” or “How do we live by and by” when the world ends. “It dread” is the answer. Burning Spear had a similar vibe, but protean and primal as the truly great Winston Rodney sounded, he is almost Alan Lomax compared to the you-are-there gestalt here. It sounds like a crashing airplane’s black box recording, if the pilots just took their hands off the controls and sang Jah’s praises.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (or at least regularly) until Donald goes away.

Sunday, August 17, 2025

109. The Red Telephone

Love: Forever Changes (Elektra, 1967);

composed by Arthur Lee

Hardly anyone bought this album in 1967, but it has never gone out of print and probably never will. Occasionally, I like to picture an alternate 1960s in which Arthur Lee and his cohort(s) had monster hits, which many of their songs sound like they had to have been. Until of course I once again listen closely and cannot help noticing that under all of Arthur’s (apparent) whimsy and (bodacious) (and jerry-rigged) tunecraft were beefs and paranoia aplenty (which ruled out doing any promotion, let alone touring outside of L.A.). And which makes it somewhat miraculous that three albums into what was already a doomed four-album contract, Elektra mysteriously shelled out for string arrangements to which Love responded with eleven perfect (and perfectly weird) songs that just samba right over your head - each one courting enlightenment while archly noting the blood coming out of their bathroom faucets. This tune ends (what was) side one, opening with a solemnly lyrical vision of nuclear devastation, followed by a playfully dilatory existential disquisition, and ending with a demand apparently copped from the Bonzo Dog Band, “We are all normal and we want our freedom.” But are we not vaporized? Maybe. So what?

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (or at least regularly) until Donald goes away.

Wednesday, June 4, 2025

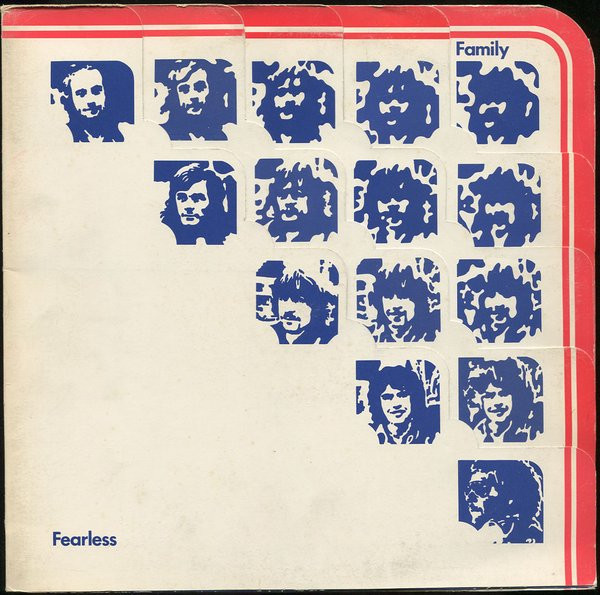

108. Spanish Tide

Family: Fearless (United Artists, 1971);

composed by Charlie Whitney & Roger Chapman

What most annoys me about the notion of “classic rock” – apart from it being yet another opportunity for nostalgic white boomers to congratulate themselves and bemoan the cultural poverty of the present day – is that it does not accurately describe a period when “rock” really did provide an avenue to all sorts of ambitious and genuinely heterodox gambits, because no one was really sure what it was supposed to sound like – even as late as 1971. Prog was just the all-too-obvious high-concept version of this hustle. More interesting were bands like this one: five Brits in a seemingly conventional rock-band configuration, except that the vocalist, Roger Chapman, sounded like he was having a seizure whenever he revved up, and Charlie Whitney’s music kept zinging in a different direction every few bars without losing overall focus or taking on any untoward symphonic airs. Or jazzy ones, for that matter, although you could tell these guys had the ears for it. John Wetton left to join King Crimson a year later, but he never sounded better with anyone than he did here – supplementing Chapman with his own foggy hoot and doubling up on bass and 12-string. But Crimson never sounded better, either.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (or at least regularly) until Donald goes away.

Tuesday, June 3, 2025

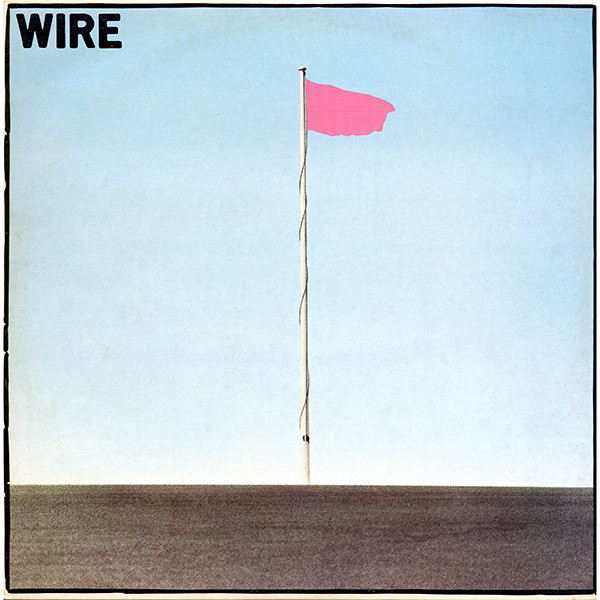

107. 106 Beats That

Wire: Pink Flag (Harvest, 1977);

composed by Colin Newman & Graham Lewis

“Primitive” is an ill-informed value judgment; “primitivism” is an artistic strategy. How few informational elements can you place in proximity to each other such that they still generate a charge? That is what punk was – or came out of – and it is also what post-punk was, which is why what distinguished them (or not) had nothing to do with chronology. Wire’s debut was an art project comprising twenty-one songs running about thirty-six minutes, each of which addressed this question with minimal drums, overdriven guitar noise, and a snarl sounding alternately sardonic and terror-stricken. The title of this track – which runs a minute and twelve seconds - refers to the number of words in the lyrics: a third-person vignette of some irritating arty type. When the words run out, the song simply stops. Notwithstanding this formal stricture, almost half of it – splitting the words into two discrete blocks - is given over to one of the most sinister rave-ups in the music, moving from the simplest descending single line tracing the notes of the major chord, and then quickly doubling to a chorded barrage that instantly feels like it is coming through your bones. People dick around while the world ends.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (on average) until Donald goes away.

Sunday, June 1, 2025

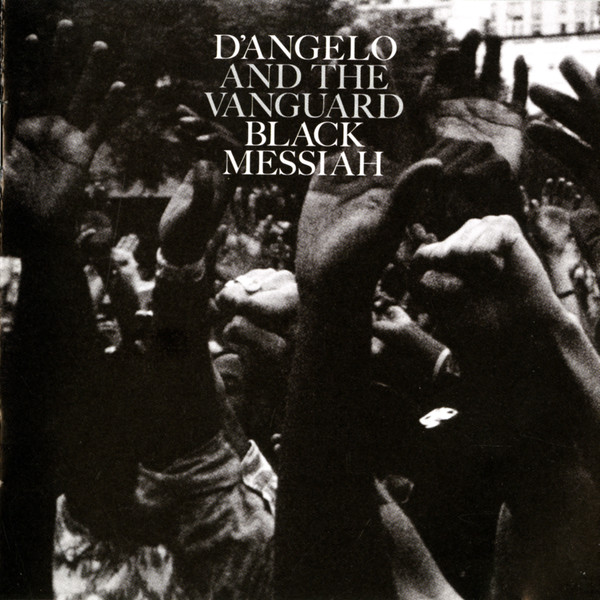

106. Prayer

D’Angelo & The Vanguard: Black Messiah (RCA, 2014);

composed by Michael Eugene Archer

All of D’Angelo’s studio albums freak me out, but the fact that he has released only three of them in thirty years is the aspect that actually freaks me out the least. Every time I hear this track from the last album he put out after a decade of silence – (reportedly, Prince had written him a letter the entire text of which was “Well?”) – my first reaction is the same: “How did they get the chiming bells in tune?” Maybe no one cares, but tubular bells have so many overtones that they always sound sour to me. No less so than the brief section of actual tubular bells on Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells.” Or Chic’s “I Want Your Love.” Not here. The tonality of the sound centers the whole track. Which suggests that D'Angelo did not get the bell in tune with the track; rather, he got the track in tune with the bell, overtones and all. What sounds like the most basic of drum shuffles by Questlove is glued to a murky electronic wash under which D’Angelo prays for his own sanity. Proof of any pudding is in the eating, but that goes double when the pudding eats you.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (on average) until Donald goes away.

Friday, May 30, 2025

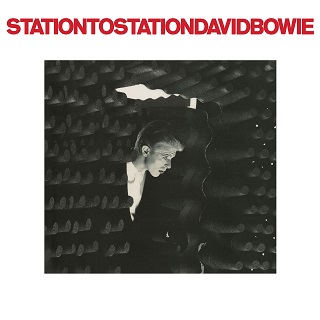

105. Golden Years

David Bowie: Station To Station (RCA Victor, 1976);

composed by David Bowie

This single – and this band - is the only fit object for the term “love muscle.” After the advent of Carlos Alomar (and a John Lennon visitation) produced “Fame,” this sequel is the first Bowie track with the Alomar-George Murray-Dennis Davis rhythm section as its foundation and substance. The lyric is another cautionary litany about fame, but Bowie’s vocal gives itself up so completely to the groove that it projects a wholly different kind of hologram than the pale coke freak he presented at the time. Alomar has been candid that Bowie hired him because he wanted to get the most then-current currents of Black American music into his sound, and Alomar was perfectly happy to do that for him as long as the money was correct. But I still think it was more than the money; after Station, this group with various guest weirdos did Low, Heroes, Stage, Lodger, and Scary Monsters – all over the place stylistically but with a bottom like death throughout. As excited as I was to hear that Nile Rodgers was coming in for Let’s Dance, what resulted (and sold kajillions) did very little for me after that end-of-decade streak. Bowie had his own Chic.

Note: Secular essays about individual songs, each one exactly 200 words long, appearing one per day (on average) until Donald goes away.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)